The U.S. Army War College, in collaboration with indigenous leaders, began their largest repatriation effort, consisting of 11 children who died during their time at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

As of 2017, the U.S. Army War College has been working with tribes to help repatriate their children who never received the traditional funeral rites of their tribes. The Army has returned 32 children in the past seven years, and according to Native News Online, has promised to “return an additional 18 children in 2025.”

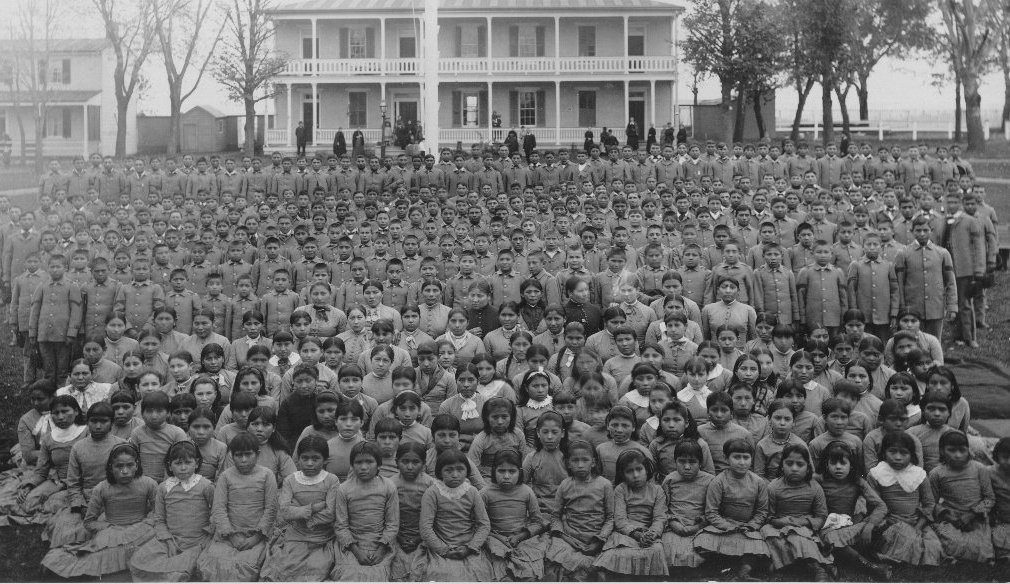

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was founded in 1879 on the site of a U.S. Army barracks by Richard Henry Pratt. Pratt, who coined the term “kill the Indian, save the man,” opened the school with federal funding as an attempt to assimilate Native Americans into white society by destroying their cultural practices.

The school operated from 1879 to 1918, during which over 7,800 Native children were brought to Carlisle for enrollment. Of those 7,800, around 780 were 12 or younger, and 5,200 were male. While it was operating, 192 children died on the premises, either from disease or abuse.

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School became the blueprint for similar assimilationist residential schools throughout the U.S. and Canada, which incorporated a similar combination of western-centric education and physical labor to forcibly assimilate Indigenous children. Amanda Cheromiah, director of the Center for the Futures of Native Peoples, elaborated, saying, “[the school] has impacted the genetic makeup of indigenous [tribes] for generations.”

The school closed in 1918, and the U.S. Army War College moved to the Carlisle Barracks in 1951.

Cheromiah provided insight into the repatriation efforts and the legacy of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. When asked what the significance of the school was, she replied that it was a symbol of Native people’s different political status, an essential part of history and a show of Indigenous culture’s endurance.

Cheromiah said that sending Native children to the school was, “cheaper than killing [them],” but while they were here, they did not allow the school to fully destroy their culture.

When asked about the significance of the repatriation, Cheromiah started with an anecdote. When she received her job at Dickinson, her mother told her not to come to Carlisle. She said, putting herself in her mother’s shoes, that “[when they went to Carlisle] a lot of Indian kids didn’t go back to their moms … or when they came back, they were completely different people.”

Cheromiah went on to say that the repatriations “give the tribal peoples authority to do [proper ceremonies] regarding their people,” and that it was an assertion of sovereignty, ceremony, and tradition. She also explained how the repatriation efforts reclaim Native stories from the school, which have often been told by staged photography, and are now being spread by relatives and the work of the Dickinson Archives.

She considers the history surrounding the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and other similar schools, “[an] essential part of history,” and that it is important to learn this part of American history to understand America and its relationship with indigenous peoples.

Cheromiah calls the current actions an “intergenerational repatriation… [which pushes] toward making experiences visible.” She explained her efforts in the repatriations as feeling as if she was standing on the edge of the Grand Canyon, and that it was the scope of what she had to deal with, but she was nonetheless awe of it.

She explained how she meets with the representatives and families of the children, saying that the process of repatriation was a process of “cultivating trust” between her, the Army War College and the families of the children. She said she feels like the Center for the Futures of Native Peoples was a “guiding light” in the repatriation effort, and that she is honored to be here.

When asked about the repatriation effort, the U.S. Army War College sent a briefing which stated that, “The return of these eleven children to their Native American families is one of the Army’s highest priorities and we hope it will bring them the long-awaited peace and closure they deserve … We will continue to work with families and tribes in their courageous undertaking to return these children home.”

The Army War College also included a list of the children being repatriated, “William Norkok from the Eastern Shoshone Tribe; Almeda Heavy Hair, Bishop L. Shield and John Bull from the Gros Ventre Tribe of the Fort Belknap Indian Community; Fanny Chargingshield, James Cornman and Samuel Flying Horse from the Oglala Sioux Tribe; Albert Mekko from the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma; and Alfred Charko and Kati Rosskidwits from the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes. One tribe wishes to remain anonymous.”

Dickinson works closely with the U.S. Army War College in these repatriation efforts. Cheromiah and the Center for the Futures of Native People help the relatives feel a sense of trust between themselves and the colleges. Jim Gerencer, Susan Rose and Malinda Triller Doran have undertaken an effort to help catalogue the documents, photos, and records which came out of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and make them accessible online through the Dickinson Archives. These documents can be found at https://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/.

The current repatriation efforts began on August 19 and are expected to conclude on Oct. 14. The cemetery on the grounds of the U.S. Army War College is currently closed to the public for the repatriations.

The cemetery currently holds 23 unknown graves, which the Army College and independent organizations are taking steps to reunite with names of students.

Terry L dasher • Oct 18, 2024 at 7:49 pm

1st time I seen died of abuse, that’s all it takes is telling the truth, I often said alot did die of disease but I’m sure there was alot of abuse there, kudos to the carlisle army for trying to do the right thing. I wish they could do the same for Jim Thorpe, that man never set foot where he is buried.