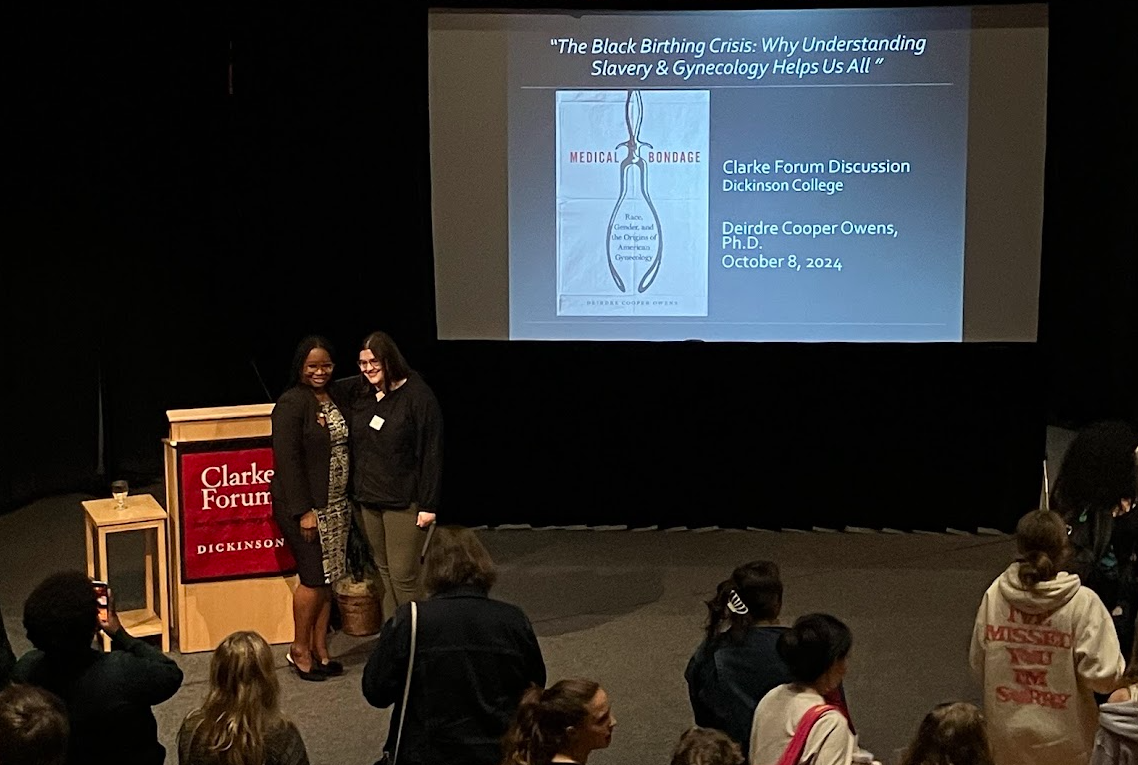

“The Black Birthing Crisis: Why Understanding Slavery and Gynecology Helps Us All,” delivered by Deirdre Cooper Owens, associate professor of history at the University of Connecticut, was a telling lecture on the historical and racial context about how Black bodies are treated in the medical field.

Organized by history major Shayna Herzfeld ’25, the intention to have open dialogues about such brutal realities in our history is vital to completing the historical narrative. One must do critical research and reflection to honor difficult histories more honestly with acknowledgement to the wrongs committed. In the words of Cooper Owens, historians must do what they are charged to do – not provide trivia, but context.

Medical racism circled back into the public eye during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ed Livingston, editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association, advertised a podcast via a Tweet, saying “No physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care?” Even more telling about the politics of white guilt is this quote from the podcast itself: “Structural racism is an unfortunate term … I think taking racism out of the conversation will help. Many people, like myself, are offended by the implication that we are somehow racist.”

Cooper Owens went on to cite jarring statistics conducted during a doctoral study headed by Kelly Hoffman in 2014. She sought to understand pain management in regard to race using fictitious patients’ responses to severe medical traumas. Her findings concluded that medical students were still following false beliefs perpetrated from medical findings from the 19th century that continue to shape the way we perceive and practice treatment on Black people.

According to Cooper Owens, historical context is the most important part that is often overlooked in how we deal with medical racism today. Samuel Cartwright was a leading slaveholding physician that sought to find the “distinctiveness of the negro from the free white.” He is best known for his invention of drapetomania, or the idea that slaves who wanted to run away was a result of mental illness.

Cartwright used a spirometer to prove that enslaved Black people had less lung capacity, a theory built upon scholarship from Thomas Jefferson and Dickinson College founder Benjamin Rush. Althoughthese were highly educated and respected men, there was a known political agenda that was encouraged and thus skewed the findings. These men knew that enslaved people were not living in the same conditions as free whites. The same rubric of lung capacity is still used today.

Historians are not considered to be value neutral, there is always an agenda behind what should be objective conclusions. However, Cartwright is an example of how science is also not neutral since he was commissioned to write his article on whether “the negro was fit for freedom or slavery.”

James Marion Sims, considered the father of gynecology, used enslaved women as the basis for his false or incomplete medical narrative. The engine of America’s wealth depended on the survival of Black babies, and thus the health of Black women was the utmost importance for economic entrepreneurs. As Cooper Owens reminded us, slavery was so successful in this country because the enslaved performed work so well.

Cooper Owens said numerous men contributed to the historiography of Black gynecology. Though Sims receives the most critiques, the focus should not be on one person as a “historical boogeyman.” Cooper Owens reminds us, “Hate Sims all you want, he’s dead.” The context of antebellum America is apparent in Sims recordings, if we are careful enough to read in between the lines and construct a narrative for the women who could not leave their own records.

Sims trained the enslaved women he experimented on to be his nurses in the first hospital for women in the United States, which just so happened to be a hospital for Black enslaved women. Sometimes, this history erases these women and paints them as white. Sims was not operating in a whites only world, and it is imperative to remember that when we review this history and avoid adding any modern lenses.

Cooper Owens said she does not receive much backlash from her teachings. Some white women will respond that doctors do not listen to all women, and that it is a gendered issue rather than racialized. However, when looking at the statistics, Black women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy related problems than white women. The issue is racism, not race, when it comes to Black maternal mortality. Black newborns are three times more likely to die than white babies, but when cared for by Black physicians, that number drops by half.

Other backlash Cooper Owens has received comes from young Black women. There was a book that had been published about epigenetics, or trauma from racism that is bound up in Black DNA and changes the makeup. To the people that believe this, Cooper Owens asks, “Are white people and Black people different biologically?” If this is your belief, Cooper Owens firmly stated that these individuals are in agreement with 18th and 19th century physicians. Though the gene expression may change, the gene itself does not.

There was a study conducted with Holocaust survivors and their children, and found that after three to four generations of not experiencing that level of trauma, the body returns to its previous state. Just like the body produces scabs to protect itself, the body protects itself from that level of trauma. Cooper Owens reminds us once again to remember historical contexts and pay attention to who is publishing these books and whether or not they are peer reviewed.

Cooper Owens urges students to read between the lines, and remember the context. Men conducting horrific experiments were doing so because of the context of the society that they were born into. What we must do today in the modern era is unlearn the history that they have built into recent generations. We are not so far removed from the 19th century as one might think. As Cooper Owens stated, “No matter our background and career, we all have the power to combat racism.”