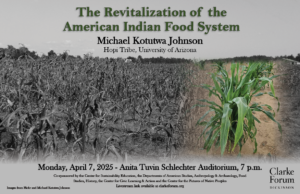

On April 7, the Clarke Forum held a talk by Professor Michael Kotutwa Johnson of the University of Arizona about ways to reform American agriculture. Johnson is a member of the Native American Hopi tribe, and he continues the tradition of farming in his background by innovating the practice.

Firstly, the professor pointed out the current state of American agriculture and the Native American communities. Agriculture in the contemporary U.S. is dominated by a handful of corporations, which pursue an approach built on monoculture that prizes a few crops at the expense of environmental safety (due to the heightened probability of a single pathogen infecting the entire field) and the risk of outcompeting smallholding famers.

The commercialization of agriculture over the last few decades has greatly disadvantaged many indigenous communities and ignored the more sustainable practices of many of these groups. Quite simply, millennia of trial and error, which correlates with the density of languages to reflect the multitude of distinct efforts, means that sustainable agriculture is actually a very old series of systems.

Johnson argues that Indigenous Agriculture Knowledge (IAK) could be used to aid the transition to more environmentally friendly and less demanding production. Notably, IAK is hardly fertilizer intensive, which reduces the costs of factory-made chemicals to farmers, and pesticides are also less needed. Local methods by the Hopi of storing sweet corn for years can also reduce the expensive warehouse requirements, which act as a barrier to expansion of small family farms.

Local strains of certain crops like corn are also comparable to what the existing industry uses. Self-pollination and shared shade are useful traits of Hopi corn, especially when confronted by a increasingly unpredictable weather pattern. These approaches can also help to regenerate the soil, rather than trying to spray excessive amounts of pesticides, which can end up harming useful wildlife. Part of the difference in approach might be to understand the different objectives of these agricultural methods. IAK strives to create survival and the preservation of traditional family units built around agriculture, whereas industrialized farming is focused on quantity and low costs, at the expense of quality.

Johnson proceeded to detail some of his initiatives and ideas. One major initiative he is a member of tries to convince seed banks that distributing their strains could provide crucial genetic material for more experimentation, especially if the strains stored are not currently in use, because there may be value that is simply overlooked. Intellectual property laws regarding seeds could also be reformed to give entire communities joint control, especially if done through an established tribe, which might encourage greater experimentation.

Scientists and Industry could also be persuaded to participate in IAK, utilizing their considerable resources to scale up the amount of land employed. Finally, more outreach could be provided to support local communities, which would encourage those not currently participating in the external sale of agriculture to get involved, as well as convincing more youth to maintain the family farms.

Johnson believes that the three goals of an agricultural system: ability to withstand climate change, empowerment for Native Americans and a less harmful approach to commercial farming, could all be achieved through IAK.