Take Back the Night, Dickinson’s annual march against sexual assault culture, occurred on Wednesday, April 9 from 7:00 to roughly 9:30pm.

Dickinson’s Campus Demonstration Policy, outlined in the student handbook and revised last fall in response to the pro-Palestine encampment on Britton Plaza run a year ago, states, “Campus protests are permitted between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. daily.”

The Dickinsonian asked President John E. Jones to comment on how Take Back the Night—which occurred as usually scheduled, outside of those hours—was reconciled with the demonstration policy.

He commented, “One person’s protest is another person’s regularly scheduled event,” and “I don’t view it that way:” i.e., as a protest. He acknowledged that the event highlights and calls attention to a particularly difficult problem on campus but reiterated that “it doesn’t fit within the rubric of the protest policy.”

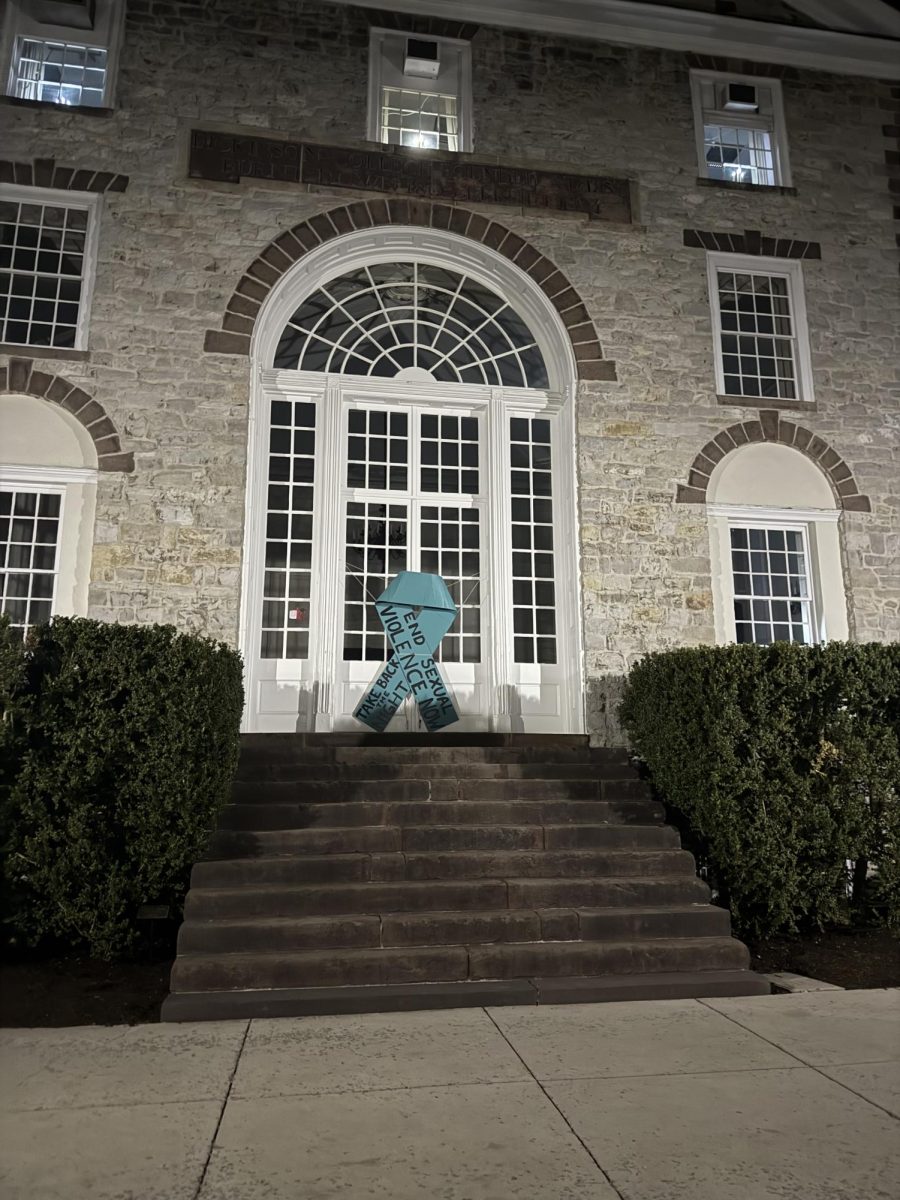

Dickinson has annually held Take Back the Night since 1988. This year’s event featured guest speaker Reverend Miller Hoffman, a performance by the Dickinson Infernos, a march and a vigil in front of Old West.

Take Back the Night is the “oldest worldwide movement to stand against sexual violence,” and came out of protests in the 1970s, according to the organization’s website.

Katie Schweighofer, director of the Women’s and Gender Resource Center said that Take Back the Night “allows us to each year decide to have this conversation about what we can do for people in our community” and “keep the energy moving forward.” Student organizer Anna Nasser ’25 said, “it’s not for anyone but the student body.”

During the negotiations between the Dickinson College Coalition for Mutual Liberation’s and the administration during and after the encampment, Take Back the Night was discussed as an example of a campus event that the new protest policy would affect. The Dickinson administration said at the time that Take Back the Night is not a protest.

However, aside from this exception, the Dickinson administration has not clearly defined what movements it may or may not classify as protests, specifically pertaining to certain club activities, movements’ sponsorship by College departments, their history at the College and other factors. The lack of clarity may lead to ambiguous consequences for students who do not follow the guidelines.

Take Back the Night student organizer Riley Heffron ’26 said, “It is a protest, and it is a show of unity … a way for people to feel seen and feel heard,” and specifically described Take Back the Night as a “school-sanctioned protest.”

Schweighofer said, “I do see it as a protest … because of what we do and how we do it … When we stand up for what is right and use our voices to claim or reclaim public space, that’s protest.” She added, “It feels like a protest to anyone who attends it.”

Schweighofer and Nasser emphasized Take Back the Night’s history in grassroots forms of protest, such as feminist and civil rights activism.

Student volunteers organize and lead Take Back the Night. Schweighofer said, “Student energy is part of that protest energy. The event works because students want to do the event, because it is about standing up to a culture that we’re tired of.”

The separation between the campus institutions and Take Back the Night is intentional because of the space for students to share stories of their negative experiences with campus organizations: “exactly why this is protest,” said Schweighofer.

Though student workers organize and run Take Back the Night, the event receives sponsorship and staffing support from the WGRC, the Title IX office and the Wellness Center.

Nasser said that Take Back the Night “sometimes has to hold hands with the people you’re protesting against” particularly when it comes to students who feel that the College has mishandled their sexual assault cases. She said that Take Back the Night has to “walk the line of not glamorizing offices like Title IX,” with which students may have had bad experiences, and that it can be “weird and uncomfortable to rationalize having Title IX be a part of that.”

Nasser said of this year’s Take Back the Night that her “biggest takeaway was being able to stand in front of Old West… being able to stand in front of the building [admin] call[s] their home and talk about our experience is something I think is really important.” Both student organizers remarked on the importance on conducting the vigil in front of such a visible symbol of the school.

Unlike other protest movements, Take Back the Night means that it works within the system of the College, which is why the administration allows it.

A major event that the organizers of Take Back the Night had to contend with this year was the August 29 arrest of Wellness Center counselor Theo Nugin on multiple felony charges, including unlawful contact with a minor and sexual abuse of children.

Nasser explained the need to “take it back for the students” after such an event. Schweighofer commented on the surprise and betrayal students and staff felt at the news and said that it makes it harder for student victims of sexual assault to trust in Dickinson’s support.

The events contributed to the chosen speaker for this year, Hoffman, who spoke about the grief and anger that arises from sexual assault.

In Heffron’s opinion, although the new protest regulations were put in place to avoid encampments, the Dickinson administration should acknowledge Take Back the Night as a protest and reform the rules to allow more forms of protest. Schweighofer also said, “If we have a version of protest as too narrow, then we’ve closed other avenues for making change.”

Prior to last year’s encampment, the most recent protest movement on campus occurred in February 2020. Rose McAvoy ’20 spoke out against Dickinson’s gross mishandling of her sexual assault case and organized a student protest that included a four-day, overnight sit-in in the HUB.

Jones, then chair of the Board of Trustees, said at the time, “it is a very complex thing, Title IX … [is a] hot button issue. I don’t think there is a university in the United States that does not find this to be a fraught issue,” as reported in The Dickinsonian

McAvoy’s sit in would not be allowed under the current campus demonstration policy. That protest was instrumental in reforming Dickinson’s Title IX policies.

Nasser emphasized Take Back the Night as a “continuation of Rose,” and that the administration’s present exception of Take Back the Night is demonstrative of “admin encouraging one form … and butting heads with another form” of protest against sexual assault culture on campus.

Schweighofer added, “I hope that Take Back the Night can be a place where students can engage in honest, truth-telling, authentic listening and reflection on what we want the world to be, and I think that is a valuable bit of resistance & I would encourage students frustrated with campus culture in other areas to find comparable forms of resistance even as they adhere to the campus protest policy.”