Since May, The Dickinsonian has been speaking to faculty and campus groups affected by the Trump administration’s cuts to academic funding. This article specifically explores the impact on humanities and language faculty.

Dickinson doesn’t rely a lot on federal funding, but faculty across campus have had their work and research interrupted.

Over a year ago, history professor Say Burgin “applied for a really prestigious fellowship through NEH,” the National Endowment for the Humanities which historically has funded much humanities work and research in the United States.

She found out that she got the $60,000 award and signed a contract with the federal government in December 2024. It was a competitive yearly fellowship, which only 6% of applicants received. It would provide her with research leave for the following school year, and because of this security, she felt comfortable to she get her paperwork in order.

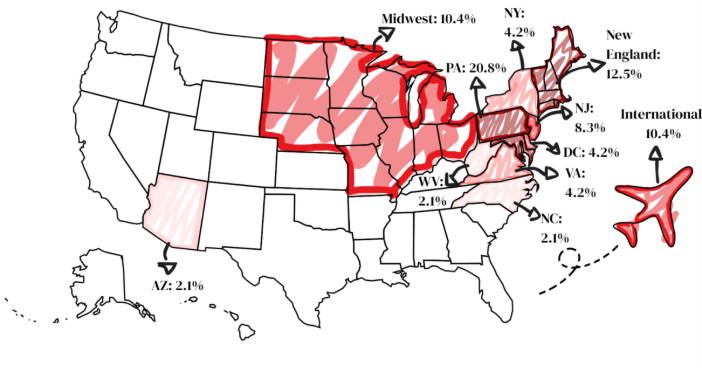

While on sabbatical, Burgin planned to work on a new book project, “Can’t Jail a Revolution,” about how states criminalized and repressed civil rights and Black power activists. She planned to visit archives in Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, Detroit, New Orleans and San Francisco. She was also planning to conduct oral histories with former activists and complete a few chapters of the project

However, in April, the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) went through the NEH headquarters. Major recipients of NEH funding were state councils for the humanities and their funding was cut. The Pennsylvania state council emailed her that their funding had stopped abruptly.

On April 4, Burgin received a form email in her junk inbox from Michael McDonald, the acting chairman of the NEH, that her fellowship was not a priority of the president and had been terminated.

At Dickinson, Burgin was the faculty member who lost the most significant amount of funding. She began working with the college right away, and the college helped her submit an ultimately unsuccessful appeal. Because she is also planning a symposium for the school, the college can continue paying her salary for the year.

The college paired Burgin with a gift the school has received instead and was fortunately able to place her on research leave for the current school year.

Professor of Spanish Mariana Past, also lost a $6,000 open book grant last January that would have allowed more people to access her upcoming translation, “Unbroken Nostalgia: Haitian Kreyòl Poetry in Cuba.”

Since then, she was able to receive $1,000 in support from Amherst College Press and $2,000 from Dickinson via a research and development grant. She plans to use half of the money she received from Dickinson to attend conferences to promote the book.

She feels “very supported,” by Dickinson, particularly since she continues to teach topics of Black power, which appear in her books. However, she plans to wait several years to apply for additionalNEH grants, at least until the Trump administration is no longer in power.

Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections has also been affected by the DOGE cuts since the beginning of the year. Dickinson is involved with the Carlisle Indian School (CIS) project, which runs the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center (CISDRC).

The National Native Boarding School Healing Coalition had received a grant to digitize boarding school records across the country, and invited the CIS project to receive some of the money as a sub grant award to pay for the indexing of digitized Bureau of Indian Affairs records, including outgoing letters from BIA officials from the 1870s and 1880s.

The materials had been digitized and scanned in autumn 2024 but indexing only occurred for the first three months of 2025.

The Healing Coalition notified the Carlisle Indian School project on April 3 that the federal government had wholly terminated the grant, of which the Healing Coalition was in the final year.

Jim Gerencser, Dickinson’s head archivist, told the three indexers to continue their work through the end of April, and paid them out of his own pocket. By May, when they formally stopped working, the indexers had indexed 10% of the 30,000 pages of digitized materials.

The indexing was not part of the core work of the Carlisle Indian School project, so it was “not as immediately damaging as it would be for other projects,” said Gerencser. CISDRC is not currently supported by any federal funding but is part of Dickinson’s regular budget.

Rather, the cut inhibits the long process of expanding and making materials about Native American boarding schools more accessible.

As of October, Gerencser shared, “there has been no change in our funding situation since we spoke in the spring. At the moment, we have no sources of external grant funding supporting the work of the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.”

“The professors I’ve talked to here are bewildered and sad and unclear what is happening,” said Burgin in May. She said that it was hard to know how to fight back and how long the cuts would continue.

Although only a small group of professors lost funding, many professors now have no more grants to apply to. According to Provost Cramer, the Faculty Personnel Committee has had to ensure that faculty are not penalized during tenure and promotion discussions since they are now unable to be active in their research.

Not every faculty member, however, has reported their funding difficulties to the school, according to Professor of Japanese Language and Literature Alex Bates, chair of the Research and Development Committee (R&D). Normally, R&D provides faculty with a smaller amount of money to jumpstart their research so that they can apply to larger state and federal grants. Now, R&D is organizing a pilot program to provide larger grants to faculty, to which they can apply once a year, though the funding is nowhere near sufficient.

An upcoming survey from the provost’s office will ask faculty in more depth about how they have been affected. Bates described the faculty mood as “discouraged, upset and confused,” and the cuts “capricious and nonsensical.”

Burgin stressed that the full impact of the administration’s attacks on and cuts of humanities research is still unknown. Over the course of the past ten months, archives and museums have had to reconfigure their budgets, storage and processing capabilities and their ability to be available to the public. She said, “the whole process of knowledge production will slow down.”

Gerencser said, “it’s going to slow down people’s work or make things not happen at all. Things may never get underway.”