Art Meets Activism in Music Department Concert

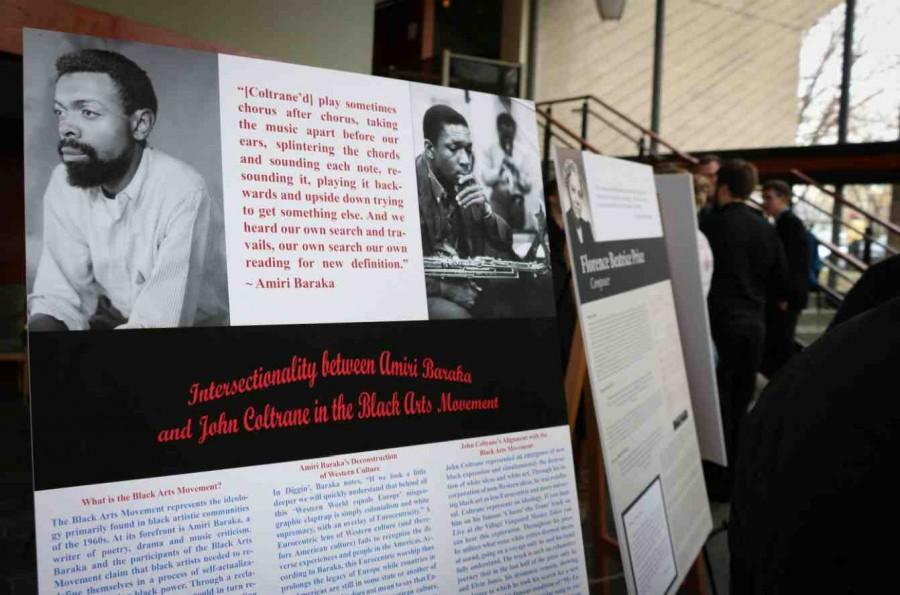

Attendees view student-made informational posters in the lobby of ATS. The posters will be displayed in Weiss for the remainder of the year.

Three of Dickinson’s music ensembles came together on Sunday, April 10 to perform “Black Music Matters,” a concert celebrating the black music that is traditionally excluded from music education and performance.

The multi-media concert featured Dickinson College’s choir, the Improvisation and Collaboration Ensemble (DICE) and the jazz ensemble along with members from Dickinson’s faculty, staff and student body. The theme was social justice in the vein of the Black Lives Matter movement, which the name of the concert invoked.

According to Amy Wlodarski, director of the Dickinson College Choir and assistant professor of music history, the idea of the concert was partially inspired by the activism of the Why We Wear Black group this past fall. Students in WWWB requested that the administration diversify offerings within the college’s academic departments.

“We took this idea of intersectionality, which had been at the heart of Black Lives Matter,…merged with this call from the students…for greater awareness to their own culture and heritage and representing their own experiences within the classroom, and we decided to do a ‘Black Music Matters’ concert,” said Wlodarski.

The concert itself was split into four sections: “Harlem Speaks,” “Queer Harlem Speaks,” “Black Bodies Matter” and “Wise, Whys, Ys: The Griot’s Song,” which references Amiri Baraka’s epic poem of the same name.

Each ensemble performed separate and distinct repertoires that drew attention to the different ways black artists have influenced music over time. The jazz ensemble focused mainly on jazz music from the 1930s to the 1960’s and the choir performed haunting renditions of African-American spirituals, described as “the rhythmic cry of the slave” by W.E.B. Dubois. DICE’s repertoire was the most experimental of the three, focusing on ambient and highly improvisational works by composers such as Florence Price, Julius Eastman and Frederick Rzewski.

Audio recordings were used to give context and commentary as a preface to each musical piece. The recordings consisted of poetry or text read by members of the Dickinson faculty, staff and student body. Samantha Miller ’18’s reading of “Flag Salute” by Esther Popel Shaw prefaced the performance of “And They Lynched Him on a Tree.” The poem juxtaposed the Pledge of Allegiance with the lynching of George Armwood in 1933, implying that lynching had become a ritual of interracial social control in the U.S. at the time.

There were historical audio recordings involved as well: the “Testimony of Witness #51 to the Attica Prison Riot” prefaced DICE’s rendition of “Chains/Attica,” a composition by Frederick Rzewski. Amiri Baraka read his poem “Africa,” which prefaced the choir’s rendition of “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child.”

Some performances were accompanied by images. Historical pictures of the Civil Rights Movement of the ’60s or the Ku Klux Klan were shown alongside modern pictures of the Black Lives Matter movement or Confederate flag supporters, suggesting that the fight for justice is not yet over.

The concert ended with a performance of “Oop Bop Sh’bam,” a song by Dizzy Gillespie, performed by both the jazz ensemble and choir. The concert was well-received by all who attended, and the performers received a standing ovation at the end of the show.

“It was very enjoyable,” said Connor Burns ’18, “For me, I’m [going to] go home and listen to some of Duke Ellington’s stuff, [be]cause it was so great. I think this was a great way to bring history and culture to campus.”

“I think part of the message of the college is to celebrate diversity in all forms, and it’s great to involve and invite the entire community to experience the wealth of cultural riches that exist beyond what people normally hear. It was really enriching,” said Phil Wolf, parent of Zephram Wolf ’16.