An Interview with Piper Kerman

The Dickinsonian sat down with Poitras Gleim recipient Piper Kerman to speak about her memoir, Orange is the New Black: My Year in a Woman’s Prison, and its spin-off Netflix series. She discusses what she thinks students should understand about the humanity of the incarcerated, and her take on identity and activism. The full interview is below.

The Dickinsonian: What was the process that you went through to write the memoir and did you know that you wanted to write one right away? Was it something that you thought about a lot or was it more of a spur of the moment decision to start writing?

Piper Kerman: I remember when I was incarcerated and living in B dorm, I had a bunkie, my bunkmate, whose name was Natalie, she’s Natalie in the book, and when things were really, really crazy in B dorm, Natalie had been incarcerated was a while, she was actually close to going home, she was an older woman, very well-respected there; every now and then things would sort of be going crazy in B dorm, she would turn to me and she would say, “Bunkie, go home and write a book,” and I would say “oh ha ha ha Natalie,” but I went home in 2005 and I was encouraged by many people to write about the experience and I was so of skeptical about that, I had never written anything for publication before, but of course I am the product of a good liberal arts education, like Dickinson. I first just sort of sat down and thought “what are some of the stories I would want to tell that someone else would be interested in listening to, what do I think would be interesting to other people?” So I wrote about the first day in prison, I wrote about Vanessa, who was the transgender woman who was another one of my neighbors in B dorm, she lived there with me for a period of time, I wrote about being put on the federal transfer system and being put on the federal jail in Chicago, because that was a very dramatic and conflict-ridden experience, that’s when I came face-to-face with my ex behind bars, so, I just wrote about some of the stories that I felt like really stood out in the experience, and that was the beginning of that process. It’s just a process of storytelling and thinking about what stories are important to you and might be of interest to other people and what’s the information that those stories carry with them.

TD: When the show came out, it was three years after the book came out, because the book was 2010 and the show was 2013, did you know when you were writing it that it would turn into a show or that it had the possibility to?

PK: I knew it had the possibility to. There was a lot of interest in the book right from the very beginning. I always say to my students–I have incarcerated students who are writing their own stories–I say to my students and I say to anyone who wants to talk about writing and storytelling that all prison stories are survival stories. Regardless of why a person is put in prison, their sentence is something they have to survive. In the case of my story, my experience, it’s really often understood as a fish-out-of-water story because, of course, we don’t really build our prisons and jails to hold middle class people and upper-middle-class people. We vastly and disproportionately punish poor people, and significantly and disproportionately poor people of color. So statistically, the likelihood of an upper-middle-class white woman ending up in prison is very slim. So, people think about my own experience as sort of a fish-out-of-water story. So, not only how will an individual person survive prison, but how will someone survive an institution which no one really expects them to be inside?

TD: Along that same line, what was the process that transformed the memoir to the incredible success that the show is, on its sixth season?

PK: Well I always say that Jenji Kohan, who is the show runner, takes the book, and she puts it in a blender, and she puts a lot of other ingredients in there, and she presses liquefy. There are things in the book that find a home in the show in one way or another, sometimes in very unexpected ways and surprising ways. You know, there are obviously some characters like Pennsatucky and Crazy Eyes, or Red, or Yoga Jones, who are adaptations of real people who are depicted in the book. And there are other characters in the show who are totally fictional and they are not from the book, per se. All of the backstories on the show are completely fictional, none of those come from the book. I’m always fascinated by the way she… sort of cherry picks things from the book and uses them in new ways. For people who are very familiar with the show, in season three, there’s this very significant scene or set of scenes by the lake because the lake plays this really significant role in season three. And for folks who have read the book, they know that there’s this really significant scene at a lake as well. The action is different, it’s not the same story, but the symbolism is the same. That’s a great example, I always think of that when I think of how the adaptation process works. It’s not about being faithful to the text of the book, it’s about keeping the themes of race and class and gender and power and friendship and empathy, and those are the themes that drive the book, and those are the themes that drive the show.

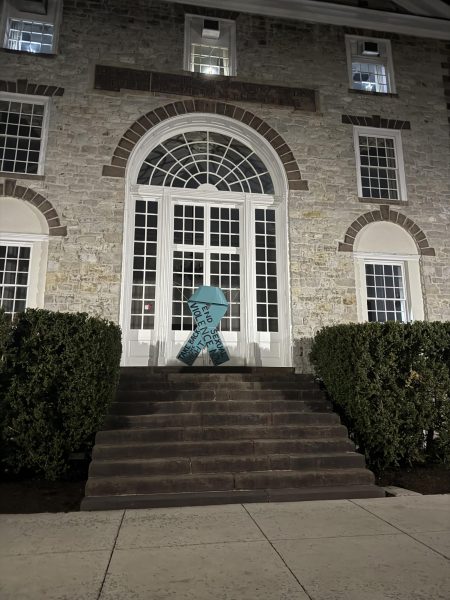

TD: How long are you at Dickinson and what are you doing during your visit here?

PK: Sadly, I don’t have a lot of time to spend on this beautiful campus, but I’m here to do this evening’s talk, as part of the annual lecture and that’s really an honor to be included in that, and I’m looking forward to it, and then back to Ohio.

TD: In the event description of the talk, it said that you’d be speaking on gender and sexuality in prisons. What sorts of connections do you hope the listeners will make between what you say and their own lives; what do you hope they draw from the talk tonight?

PK: That’s a great question. I mean, I always hope, part of my goal in writing the book and part of my goal in allowing it be adapted, was for more people to recognize the humanity of people in prison, or in the criminal justice system, and more people to be able to imagine themselves in those people’s shoes to have that level of empathy for them and to also recognize that it could be them. We want to have a criminal justice system, wherein if someone we love ends up in that position, we wouldn’t fear for their lives, we wouldn’t fear for their safety, we wouldn’t fear for their sanity. We wouldn’t ever want someone we love to go into prison or jail and come out in worse shape that they went in, but that’s exactly what happens far too often. So, the real goal in writing that book was for people to recognize the connection that we have to one another, regardless of where we stand, and to think long and hard about why on earth the United States incarcerates more of its own people than any society in human history has ever done because that’s a really significant thing. We can’t really claim to be the land of free where in fact we’re the land of the incarcerated. We are a prison nation in comparison with all other nations in the world, by far, and historically you can’t find another society that has ever chosen to do what we’ve done to ourselves. And that’s really important, and that of course relates to gender because prisons are institutions that are literally constructed around inequality; the inequality between the incarcerated and the jailer, the inequality between the incarcerated and the free, and so when we look at gender, when we look at the intersectionality of gender, and race and class, and we look at prisons, we see something very sobering and eye-opening. And of course, women have been the fastest growing part of the prison system for decades now.

TD: Something that we talk about a lot on this campus is the concept of identity, and so since you are going to be speaking specifically on gender and sexuality, and since that’s what a lot of your work relates to, I was just wondering if you could share a little about what the idea of identity means in terms of what you’ve experienced throughout your life, specifically with your incarcerated experience.

PK: I mean to me, this always really comes back to sort of narrative and story, I guess because of the way I do my work. This question of the stories that we receive about the world and specifically about ourselves and our place in it. We start hearing stories when we’re very, very small and of course those stories help explain the world around us, but they also explain who we are. And then, at a certain point in our life, we begin developing our own stories about who we are. And that story is always changing because we are always changing, we are always growing. Some people’s stories change more and some people’s stories change less, if that makes sense. In other words, people’s conceptions of themselves can sometimes become very altered in a variety of ways over time as they gain more experience, and sometimes not, and that’s a pretty interesting thing. You know, when we think about crime and punishment and safety, one of the most interesting concepts that I’ve recently come across is this idea of desistence. So, if you look at my own story, I was involved in crime when I was 22, when I was fresh out of college. I was able to, with help from people who cared about me, to desist from those behaviors. And that’s really what we ultimately want from everybody. We get a lot of focus on external factors controlling crime or determining safety, but at the end of the day if someone is involved in a harmful behavior, you know, whether that’s taking drugs or participating a gang, or whatever, we want them to be able to desist from doing what harms them or what harms other people. And some of the research around desistance, most of which has been done in the United States, some of which has been done in the United Kingdom, indicates that story and narrative plays a really strong role in a person’s ability to desist. In other words, their story, the story of their past and the story of who they are in that moment, has to change for them and they have to be able to develop a new story going forward, which is a truthful story, an honest story, an authentic story and something that they want for themselves. But that’s really interesting to me, particularly given that I teach narrative and nonfiction writing in two state prisons. So, the goals of my classes are really around creativity and education, academics. I’m not a therapist… if the work that I do has some sort of rehabilitative value I’m delighted, but that’s not really how I think about the opportunity for my students… I heard that research on desistence and I was really intrigued by it because that idea is applicable to all of us, no matter what our circumstance, the idea that we are constructing our own selves via our stories. The stories from our past, the stories that we are telling ourselves about whatever’s happening right now, and the stories that we envision for our futures.

TD: You are well-known for your activism, specifically in the field of prison and justice reform, we’ve already talked about that a little bit, what sorts of messages or advice would you have for students who are trying to be activists either in that field or with other social justice aims?

PK: Activism is just really about a combination of being of service and finding a way to transmit ideas and information to other people, for whom they might be new or for whom they might be challenging. It’s some combination of being truly of service to others and helping to find a way to spread good information, truthful information, useful information, transformative information, and translating that into action. So, I think that one of the most important starting points, especially when you’re young, is that question of being of service and how your own actions contribute to the wellbeing of other people.