Dickinson’s History with Slavery Informs Cooper Hall Name Change

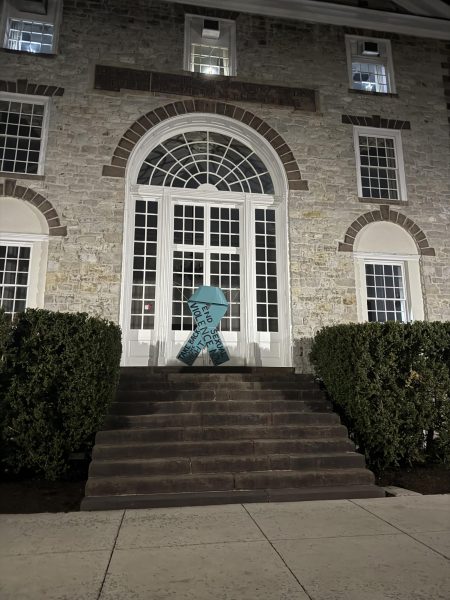

Administration is on board with changing the names of Cooper Hall and other buildings on campus named after former slaveholders, pending the submission of reports by the House Divided Project and Student Senate.

“You send subtle messages by who you honor,” said Brenda Bretz, vice president for Institutional Effectiveness and Inclusivity, “It gives us a chance to as a community to say we want to make a statement of who we are.” The reports submitted to her will go up the chain from the President’s Commission on Inclusivity to the board of trustees, who are already cued-in on the conversation, she said.

Student senators have been researching black alumni to take Thomas Cooper’s name on Cooper Hall, which was named in the 1990s, and are drafting a report this week to be sent to the commission, according to Keson Bullock-Brown ’19, senate’s director of inclusivity.

The House Divided Project has published their findings on some of Dickinson’s prominent historical figures on their website as part of their “Dickinson and Slavery” exhibit. They will submit a report to Bretz by the end of the spring 2019 semester, according a post on the House Divided website, written by Matthew Pinsker, House Divided director, Dickinson professor of history and Pohanka chair in American Civil War History.

House Divided found John Armstrong, James Buchanan, Thomas Cooper and John Montgomery, all of whom have buildings named after them on campus, were slaveholders or pro-slavery figures who never renounced slaveholding. The project also found that three other high-profile Dickinsonians – John Dickinson, Benjamin Rush and James Wilson – were slaveholders who freed their own slaves and came to renounce slavery.

House Divided has invited Carlisle and Dickinson College members to answer a few questions through its “How Should We Remember?” page, namely if the school should rename or remove memorials commemorating Dickinson slaveholder or add any memorials to former slaves or free African-Americans who worked at Dickinson. Anyone can submit their comments to the website or [email protected].

Pinsker said House Divided will also present their findings at the upcoming May 9 Carlisle Borough Meeting.

“I think it’s a wonderful thing if we want to be part of [the Carlisle] community to let them know this is happening and why, and maybe it’s to educate in both directions,” said Bretz, but “would they be able to pressure us not to do what we wanted? I don’t think so.”

As part of their exhibit, Dickinson and Slavery shone a light on three former slaves and members of the Dickinson community: Noah Pinkney, Henry Spradley and Robert Young. Bretz said administration will likely rename the buildings based on House Divided and Student Senate recommendations, also considering that donors don’t seem interested in giving a lot of money to the school to put their name on an existing building.

“We noticed the disparity between somebody like Cooper, who was a relatively minor figure on campus, compared to the important contributions made over decades made by these former slaves,” said Pinsker.

Pinkney was not an employee at Dickinson but he and his wife, Carrie, sold food to Dickinsonians for over forty years, according to the House Divided website. He was born a slave in Maryland in 1846, then served in the Union army in Pennsylvania. Dickinson installed a plaque in Pinckney’s honor near East College in 1951.

Spradley also served in the Union army. He was a janitor at Dickinson and “was among the most popular figures on campus… and a leader in the local Carlisle community,” according to the House Divided website, though “today even his headstone is missing from his former cemetery.” The college closed for his funeral in 1987.

Young started at Dickinson as a servant in the president’s household and worked his way up to campus policeman, said Pinsker. Young’s family helped integrate Dickinson and other schools in the area, according to the House Divided website, though Young “has not [been] remembered by the modern institution at all, and often gets overlooked or misidentified in photographs that remain from his era.”

“As usual at Dickinson we cover the whole spectrum,” as to who gets commemoration, said Pinsker.

House Divided invited Christy Coleman, the CEO of the American Civil War Museum in Virginia, to speak about Civil War memory from the same lectern used by Abraham Lincoln to give his 1863 Gettysburg Address.

The divide between the North and South was more complicated than mainstream narrative suggests, said Coleman on Saturday, March 23. “When we go through trauma we have a tendency to want to weave together… to explain [history] in the simplest terms, to find the good guy,” said Coleman, but “the convenient lies we have told ourselves for comfort in the end cause more damage.”

An audience member asked about the right way to handle monuments of Confederate figures. “I think this is a decision each community needs to have with themselves,” said Coleman, “I don’t think there’s a one-size-fits-all [solution] and there shouldn’t be.”

Coleman said it is “foolish to say we’re like ISIS if we take down statues,” given the oft-repeated comparison between the Islamic State’s destruction of cultural heritage sites in Iraq, Syria and Libya. “The U.S. has been taking down and putting up statues for [our country’s history],” said Coleman.

“You can’t go back and re-write history,” said Bretz, speaking about Cooper Hall. “I think we have to be really careful about applying today’s awareness and sensitivity and understanding about things and faulting someone’s actions from the past about that,” she said, “but we can bring a 21st century response to these things, and put them into historical context.”

More information on House Divided’s Dickinson and Slavery exhibit can be found on housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/slavery.

iliyana • Apr 10, 2019 at 5:25 am

It’s quite interesting. I found lots of information from your site which is very useful. I am glad that you have shared this amazing blog. https://www.promoocodes.com/coupons/active-target-promo-codes/ keep this up.