The Last Headstone: Student Documents Carlisle’s History with Race

Senior theater arts major Kenya Bullock recently made a short documentary on Lincoln Memorial Cemetery, a formerly all-black cemetery in Carlisle that was turned into a municipal park in the 1970, titled The Last Headstone.

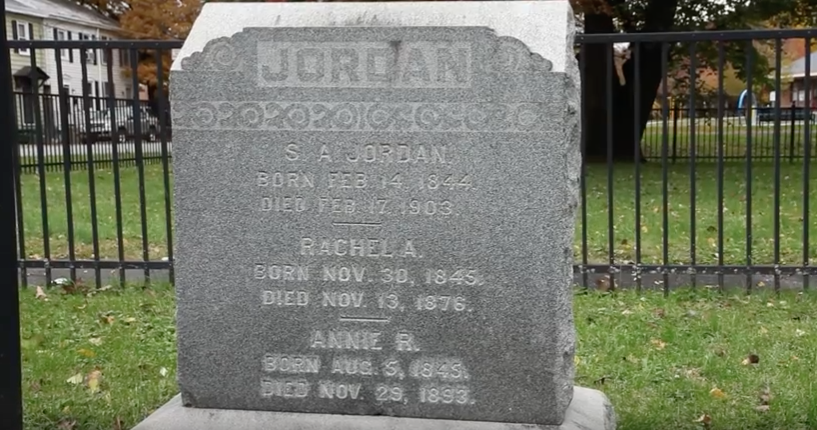

The eight-minute video tells the story of the last tombstone left on the property, belonging to the Jordan family.

“Since Carlisle has been home for four years I felt an obligation to put this story out and educate the folks that are living here and attending Dickinson,” said Bullock.

The Carlisle Borough took ownership of the cemetery by 1970 and tombstones were removed, according to Bullock’s documentary.

Carlisle resident Fleta Jordan petitioned the Carlisle court to allow her family’s headstone to remain, and it stands alone today. Bullock interviews Jordan’s great-granddaughter, TaWanda Hunter Stallworth, in her documentary, who said Jordan was “known for being engaged in the community and speaking out and speaking up for people of color.”

Bullock explores Cumberland County’s treatment of the headstones and the black people buried in the cemetery, some of whom fought in the Civil War. Bullock found that the headstones were said to be headed for another Carlisle cemetery, Union Cemetery, but in fact were waylaid for a few decades before being destroyed.

Stallworth said it was “not very likely” that the people buried in the cemetery.

“To be robbed of your dignity… during your lifetime is awful. To be robbed of that dignity again in death is also significant,” said Stallworth in Bullock’s documentary.

The Last Headstone was Bullock’s project for a documentary course with James Guardino, professor of film studies. “[W]e wanted to sort of pick stories that connected to the Carlisle community. [This story] really touched home because I am passionate about telling the stories of those that are being semi-erased from history in places that I occupy,” Bullock said.

Bullock researched for, filmed and edited the documentary. She explained her consideration of Jordan’s story: “I contacted the family, we really bonded, we created a relationship with each other, one that was of trust so that they could hand their story over to me and leave it in my hands.”

Bullock said she tried to bridge the gap between Dickinsonians and residents of Carlisle, and suggests the same for other Dickinsonians. “I know that a lot of people say this, but it’s very important to create relationships…with the folks that are surrounding us, because we are taking up a big chunk of their town and it’s important for us to connect back and show that we have that love for them and we appreciate the welcoming of Dickinson students into Carlisle,” she said.

Bullock also said filming a documentary required figuring out “how to stay neutral because it was something that I started to care about very deeply and it was an injustice to the families that are descendants of the folks who are [at the cemetery],” Bullock said. “I knew that it was important for me to keep a positive light on everyone that I interviewed and also the Carlisle Borough because sometimes it’s easier to educate coming from a neutral perspective than to attack another party.”

“[The Last Headstone] is sort of a thank you to the residents of Carlisle for allowing me to exist here,” said Bullock, “and it’s a thank you to the Jordan family for allowing me and trusting me with their story.”

Miggie • Apr 13, 2019 at 10:21 pm

Hello, where can i find a copy of the film? I would love to watch.