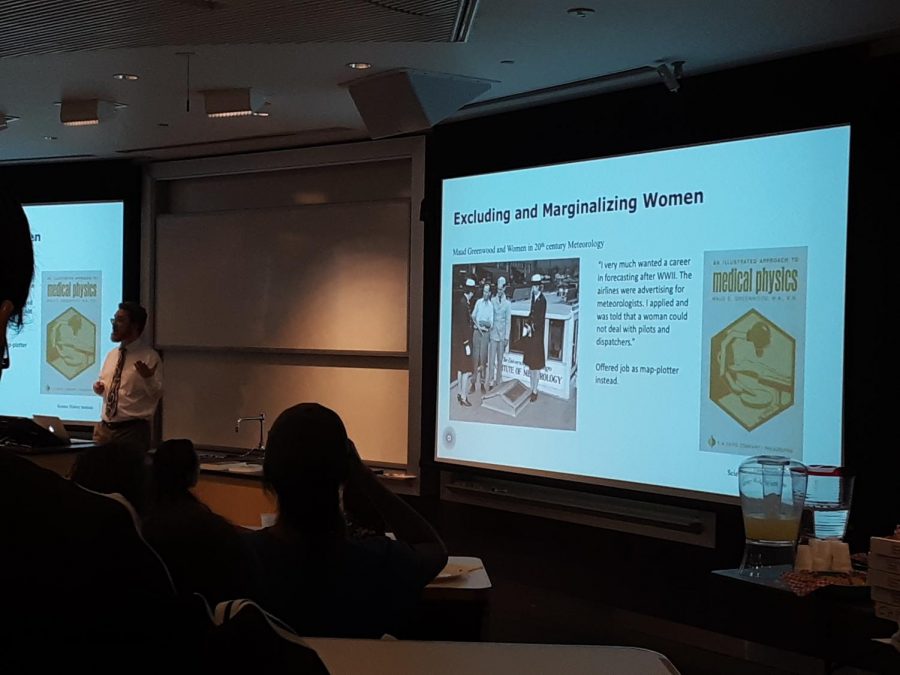

Women Marginalized in Science: Historian Presents Work

A historian of science presented his research on how women have been erased from science history or excluded from the field.

“When we think about the debates that are going on about women at the [National Academy of Sciences], the MeToo movement… online presences that are really attacking women like Dr. Katie Bouman,” a leader of the team that developed the first image of a black hole, “what are the gender dynamics in science?” asked Roger Turner, research fellow at the Science History Institute.

“Part of those come out of the stories we tell about the past,” said Turner.

Turner said women’s marginalization in science has been “particularly powerful” from the 1850s to now. He said women’s work has often been ignored or trivialized compared to that of their male counterparts. “Women’s work has not been celebrated, and it’s not been recognized as science,” Turner said.

He also spoke about the difficulty of researching women’s contributions to science, given that women often weren’t named in historical documents. Robert Boyle is immortalized for his “Boyle’s Law” on the relationship between the volume and pressure of confined gasses, said Turner, but his sister, Katherine Jones, had a significant influence on her brother. Turner said Jones was referred to under the code name “Aquarius” in her brother’s writings.

Women computers were often nameless in historical photos, and even thought to be staged models, said Turner, which historians are discovering not to be the case.

New research methods “challenge the idea that science is an activity that is free of social bias and is politically neutral,” said Turner. Women in science still face obstacles.

The modern scientific community is also facing challenges in that women in the field are seen as threatening or less serious and committed than men in the same positions, said Turner. “That’s changing over the past 40 years or so but it’s pretty slow,” he said.

“It’s been quite well documented [by sociologists of science] that a handful of women in a field doesn’t threaten the perception of gender dynamics,” but “men feel a room becomes a majority of women long before the room numerically becomes a majority of women.”

In the last four years, 28 percent of female Dickinson graduates graduated with a STEM major, compared to 27 percent of males. Of the STEM majors themselves, 58 percent were female while 42 percent were male. In terms of ethnicity, 71 percent of STEM grads in the last four years identified as white, and the remaining 29 percent identified as non-white.

Turner also touched on sexual harassment in the workplace. “Sexual harassment is also a… [part] of this story of exclusion and marginalization,” he said. It’s difficult to track throughout history, said Turner, because sexual harassment was rarely reported or recorded. It was a “very strong taboo that we’re only beginning to challenge even talking about,” he said.

Turner stressed the importance of “actively looking for women in the history of science. This is a thing that you have to consciously do.”

Turner shared the stories of a few key women scientists from the 1800s to the 1950s, and Sarah St. Angelo, associate professor of chemistry, said after the event, “it’s always interesting to hear stories that aren’t told often, as much as they should be.”

Turner spoke as part of the science departments’ recurring “Rush Hour” series, when speakers are invited to present on all things science.

“I knew [women’s marginalization in the sciences] was happening – it’s not a new idea,” said Keefer, though, “it’s good to see they’re actually doing something” by having a presentation.

Imani Whitfield ’20 said as a woman in the field dealing with a male-dominated industry, “we’re used to this by now.”

The event was held on Tuesday, April 16 in Stafford Auditorium in Rector.