Lecturer Argues for “Citizen Scholars” of Classical Literature

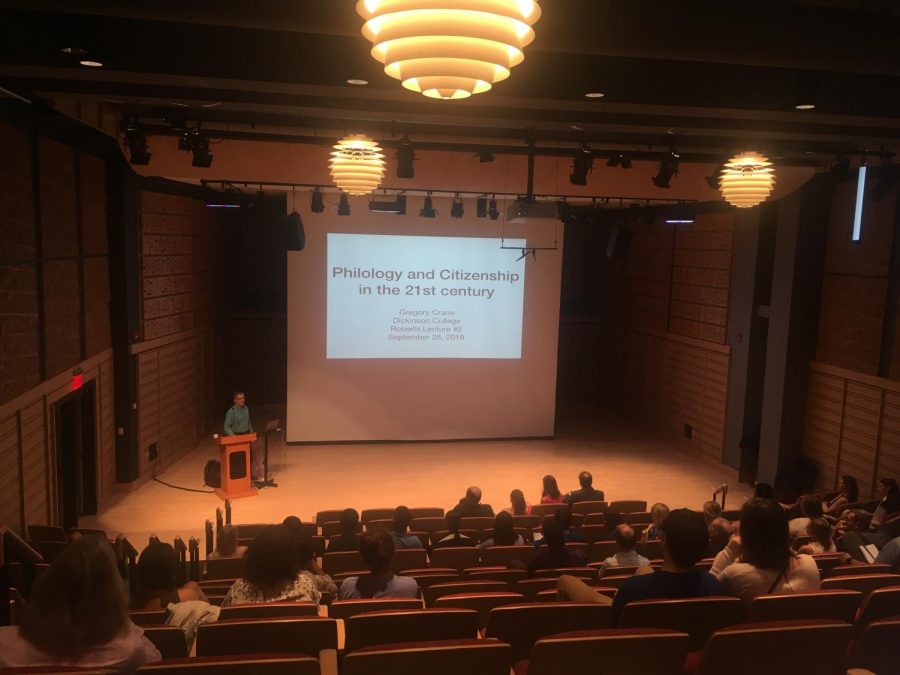

Professor Gregory Crane of Tufts University spoke about his work in “computing the humanities” during the 22nd Annual Christopher Roberts Lecture series. Crane delivered two lectures, the first titled “The New Digital Philology in the Intellectual Life of Humanity,” and the second “Philology and Citizenship in the 21st Century.”

Crane opened his lecture by arguing that the present is a good time for classicists due to the emergence of computer technologies aimed at language embedding, the ability of computers to process, model and comprehend natural human languages through artificial intelligence. He explained the significance of this through an analogy to Netflix: he argued that, to remain competitive in its market and raise its stock price, Netflix needs to expand its market share. However, it already saturates the English-speaking market. The solution is therefore to use successful tropes in existing English language productions, and applying them to foreign language shows, to appeal to a wider audience. Crane explained that it is this model he seeks to apply to the study of classical literature; rather than require aspiring students to first learn the traditional languages of classical studies, French, German, English and Italian, he seeks to develop direct translations and commentaries on texts in other languages. Computer aid in this allows for greater accuracy in recognition of words and grammar, and according to Crane, “accuracy is money and money is everything.”

However, Crane noted that the computerization of this project presents unique challenges. He referenced the definition of philology used by Augustus Boeck, a 19th century scholar, who argued philology is greater than the study of words, rather “it is the lived understanding, in the human brain. It means that something is happening in the human being’s mind.” The issue, Crane noted, is that with words and languages there are complex nuances and contexts which govern usages and forms, and that “most emotional terms do not translate properly,” issues which are solved naturally by humans, but with which machines may struggle.

Crane explained that this project seeks to both revitalize a now lost international community of scholarship based on the use of Latin as a lingua franca, but also to allow the study of classical languages to move beyond their traditional bounds. “Latin allowed you to be bigger than [an individual] It lifted you out of your local context, and put you in a frame of mind that was cosmopolitan,” Crane stated, while explaining how, prior to the Napoleonic Wars, Latin had been the language of government and higher education in Europe, most notably in Germany. However, following Napoleon, states sought to assert their own honor and national pride through their scholarship, leading to the replacement of Latin as a common tongue with vernacular languages, as European states sought to insert their own identities into these realms. This project seeks to reverse this trend while expanding the range of classical languages available to scholars, and to reintegrate the study of secular and religious texts, which became separated during the post Napoleonic shifts.

It is the scope of the project which makes use of computational comparisons a necessity, Crane explained, noting the existence of hundreds of thousands of Latin language documents in Germany alone. “This is the starting of the rewriting of intellectual history, and no one is using it.” Crane noted another issue with doing this project with humans is that “you cannot possibly master all of the languages that are at play in a complex network. […] there’s always another language.” Expansion of the corpus to include classical languages beyond Latin and Greek, notably Coptic, Persian, and the languages of India, China, and South Asia, requires the use of computers. Humans would only be necessary to begin the projects, so that once computers are able to sufficiently understand the language, they can begin their task of working regardless of modern political divisions. Crane explained that the goal is to eventually have these texts reach the level of human translators, with the ability to communicate the human element of languages across cultures, capturing the oddities, complexities, and cultural norms which govern the usage of language, to place philology within a global framework.

Students reacted positively to the first talk. Natalie Ginez ’21, added that “Crane’s lecture was very engaging and intriguing. His passion for his work with philology and especially the digital humanities clearly shone through.”

The next day, Crane continued to explain his research on computer understandings of language, seeking to “change from [he] call[s] uncharitably the bureaucracy of learning to citizen scholars in a republic of letters.” He expanded upon points made the previous day, speaking of the creation of a more collaborative environment for citizen scholars, rather than restricting the study of classics to those able to publish esoteric journal articles. “This reflects new kinds of collaborations,” Crane added, “There is something everybody can do to contribute to our understanding of the past.”

Crane explained his work in not only scanning Latin texts from early printed books, but also scanning the handwritten annotations of the owners of those books. The copying and preparation for publication of these annotations had previously been done by individuals. However, this sort of work was not common, leading to most annotations not being available for scholarship. This lack of availability hampered the ability of scholars to make use of those resources, instead relying more heavily on the text itself. “For most people […] they’re going to want to have [commentaries and] resources to understand [the text],” Crane argued, noting the difficulties in how one “connect[s] [the text] to [the commentaries].”

According to Crane, texts scanned by current computers have a 98 percent accuracy in their character identification, and are able to mark those characters the computer believes are wrong. This allows for the scanned texts to be compared against other editions, and errors are then corrected by humans. Crane noted that a 98 percent accuracy rate is sufficient for humans to read and correct the texts, and those corrections can then be used to further improve the abilities of the computers.

With this level of accuracy, Crane explained that it is possible to explore where classical texts are cited in later works, and which sections are more heavily cited than others. This allows researchers to know when particular texts are quoted and misquoted “over several hundred years and in three different languages.” “This is like the Hubble telescope,” Crane explained, “This is a system for exploring the influence of text.”

Another form of research allowed by computer analysis is, according to Crane, the plotting on a map the location of every site mentioned in classical literature. He explained that computers “can do this stuff automatically,” leaving humans to fix the errors. These advances “transform the set of people who are able to contribute” to the understanding and writing of classical text commentaries, and allows for a move away from strict literary analysis. “Many [classicists] have been too textual in our approach to things,” Crane said, “New tools are at hand to fashion new forms of literacy. We need to work with our audience, our students, and other people committed to the texts.” Crane ended his talk by noting “We have an opportunity to give students the opportunity to see themselves as making a difference.” “Anything that is useful is fundamentally satisfying.”

Reactions to the second lecture were equally positive. Assistant Professor of Classical Studies Scott Farrington stressed the importance of these computer system for “anybody who wants to read Latin or Greek.” Farrington added “that’s an important thing because […] Latin and Greek have been used to keep people away from classical studies. So I think that’s an exciting way of looking at the best use, the best application of technology to traditional humanities subjects

Chloe Warner ’20 added “The lectures really emphasized the idea of cross-language translations being a problem in today’s technological society. It was a bit saddening to realize that the world is so dominated by the English language that those who do not speak it are all so limited and cut off from educating themselves on other languages, even those that are so old that it would seem that there has been enough time to translate them extensively.”

Professor of Classical Studies and department chair Christopher Francese said “When you study classical texts it is easy to think that everything has been done already. Gregory Crane is inspiring because he shows that we’re only just getting started exploring the possibilities of global cultural understanding through language and the study of ancient texts. Crane’s idea that everyone can have citizenship in the republic of letters–where citizenship means making a contribution–is profoundly inspiring to me as a teacher and scholar.”

These lectures comprised the 22nd Annual Christopher Roberts Lectures. Crane is a professor of classical studies and the Winnick Family Chair of Technology and Entrepreneurship at Tufts University, and the Alexander von Humboldt Professor of Digital Humanities at the University of Leipzig. The lectures took place on Friday, Sept. 27, and Sat. Sept. 28, at 4:30 p.m. and 3:00 p.m., in Althouse 106 and the Rubendall Recital Hall, respectively.