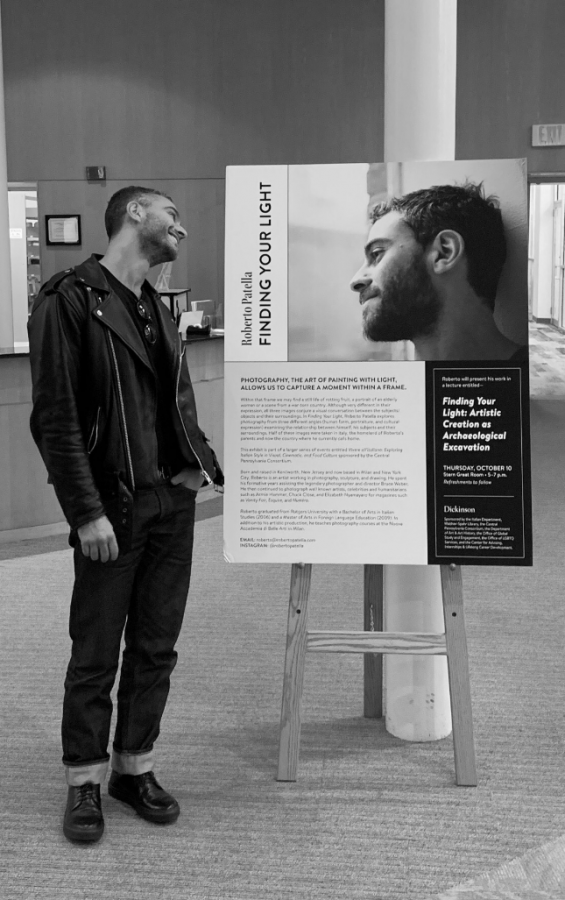

Roberto Patella: An Interview

Roberto Patella is an Italian-American photographer who currently lives in Italy. During his junior year of college, Roberto studied abroad in Florence, Italy, and shortly after he came out as gay to his family. The Dickinsonian sat down with Patella to talk about his coming out process, his work in photography, and his identity as a gay man.

TD: Can you talk a little about your upbringing?

RP: I’m an Italian-American, born and raised in New Jersey to immigrant parents. I’m from a suburb of New York City—Canerworth, which is a small-working class town. I went to public school my entire life and high school was an interesting situation because it was a small student body. There were 60 kids in my class, everybody knew each other.

TD: You mentioned that you came out as to your family while studying abroad in college, can you talk about that decision?

RP: I did four years at Rutgers [University] for my undergrad but one of those semesters I studied in Florence, but came home because I came out to my family. But I only came out to my mom when I was 20. I came out to my dad when I was 30.

TD: How was the coming out process for you at the time?

RP: [My] immigrant parents, not dismissing their intelligence at all, they spend a lot of time amongst fellow immigrants, and so they had [a] more outdated ideas of what life is and should be. Back then, being gay wasn’t out in popular culture, they didn’t real talk about it on television. There weren’t [many] gay actors, characters in TV. So, it was very difficult talking about that [being gay] in the home, for me at least. I have friends that came out when they were sixteen at the same time.

TD: Do you think that going to Italy and getting out of your home helped you feel comfortable sharing your identity?

RP: I think stepping out of my element in general, whether it was going to be Italy or another place was definitely necessary. I think for a queer person it has to be—it’s a good idea to get a better sense of what’s going on in the world, especially when you’re from a small town like in New Jersey. You realize where you come from, you have that perspective, and you realize where you want to go—what makes you happy, what’s going to make you feel comfortable and safe in the world in your own skin.

TD: After you came home and graduated from college, what did you do?

RP: I went and started working at a photo studio in New York City that shot E-commerce. So, I was in between New York City and Jersey City. I started building a life in New York City. It’s the City to be in and the easiest choice to make.

TD: How did your work and photography evolve from then until now?

RP: I think this also has to do with the question of being gay. I think we learn from such a young age to create characters of ourselves that make other people feel comfortable. My photography back then was like me pretending to be somebody else. When I first started taking pictures, my photography was very genuine and sincere, I was exploring myself. Then I went to New York and was like “oh photography is fashion photography.” So, I started taking pictures of fashion, and it was the worst work ever which is terrible—they shot in digital, the colors were awful, the tones weren’t right, the moments weren’t captured. So, I stopped taking pictures. I sort of forgot about the pictures I was taking at the beginning when I started picking up the camera and thought “wow this is magic.” Now, it’s gotten back to that sincere place.

TD: Can you talk about your nude portraits that are displayed in the library?

RP: I think American culture…we have a tendency to be a little brutish when it comes to nudity. But the nudes that I took there—it was just a project that I was working on exploring the human body in photography and exploring my limits and the limits of others—and of course, it’s not sexual but it is. We are sexual beings so why not admit it—so it does have to do with sex, but also with expiration.

TD: And that’s the human body project that you said earlier you’ve been working on?

RP: I continue to take pictures on the human form, that’s not going to stop. I think the way the light falls on the human body is incredible and beautiful. The ways that you can look at a human body through the sun and light and how it caresses the body is beautiful. It’s wonderful to look at it [the nude portrait] because it doesn’t shock you, because it’s who we are.

TD: Do you feel safe/comfortable being an openly queer person living in Italy?

RP: I don’t feel scared at all. I walk around holding hands with my boyfriend. Maybe it’s a little bit unsettling, but what I’ve noticed is if we walk around with a sense of security with who we are and with natural instinct, people respond to that. You’re holding your boyfriend’s hand because that’s the natural thing to do. It’s hard for it not to be a political statement, and that’s okay because I guess it has to be. But, if you’re natural instinct is to hold your lover’s hand in public it will come forward that way and I’ve never had a bad experience.

TD: How did you meet some of the famous people you’ve photographed like Tommy Dorfman and Armie Hammer?

RP: I met Tommy through a magazine called Rollercoaster, which is based in the UK. And they wanted to shoot them for their work with Fendy and their acting work—they had a lot of momentum. Tommy has a contract with Fendy [Beauty], so Rollercoaster wanted to shoot them to do a special for Fendy. Rollercoaster asked me to shoot Tommy because they were going to be in Milan. We shot them in my friend’s apartment where we set up a whole photo studio situation. It was a commissioned job. Tommy is a very fun subject. Armie was another commissioned job. That was a really fun job to do. Armie is really pleasant to shoot. And the fact that I was shooting film, he was really into it. When you work with these people, you think they’re divas, but usually they’re not. My experience so far has been really great. Usually it’s their whole crew that poses a lot of issues, so when I was shooting film, they [Tommy and Armie] both were happy shooting film. As I said before, when you’re working with a subject you want to be present with them, and it’s hard to be present with them when you’re looking at a screen, and it’s hard for them to be present for you when they’re just waiting around.

TD: Do you consider yourself a famous photographer?

RP: No. I don’t at all. I don’t consider myself famous, I’ve shot famous people, but I’m not a famous person.

TD: Is it ever your goal to become a famous photographer?

RP: My goal is to support myself. My goal is to take beautiful pictures, feel the butterfly feeling when I take a picture—that is my immediate goal when I take a picture. It’s like a high. Of course I have to get paid. But I’m not in it for the fame—that’s not what I strive for. I just want to make a living, I want to be able to buy a house and have a dog.

TD: How do you tell people that you can still make a living while pursuing your passion?

RP: I think in the Western culture, we are very tied to money. We are going to invest in what we know is going to have a return. There’s really no security in anything. You should always follow what makes you feel alive. What gives you that drive to wake up in the morning. If you love punching in numbers, then do it. If you love painting nails for a living, then do it. But do it with passion because it’s what you have to do in order to live. We are distracted by other things—we have a lot of options—it’s beautiful but it can also be a downfall. As young American students we can study anything and that’s beautiful. A lot of times we are driven by our parents and we are connected to them, but we feel obligated to come out with a degree to help pay our bills, and that’s functional and practical. In the end, what is success? Is it tied to the amount of money you make? Is success tied to your relationship, how happy you are in life? It has to do with a lot of that stuff together. You can’t deny the fact that we are connected to money, and that’s how our system is operating. But I think we have to follow what is right in that moment because in five years we don’t know what fruits we will receive from those decisions.