Honoring the Hallowed Ground in Carlisle

A monument dedicated to the Cumberland County soldiers who lost their lives fighting on behalf of the Union stands firmly on the corner of Hanover and High street. At the base of the structure, four miniature American flags slope above copper plaques that are inscribed with a long list of names.

Situated just beside the monument, the red-brick old courthouse is accented by sandstone columns, and capped with an ivory bell and clock-tower that overlook the rest of the town.

Herein lies the nexus of Carlisle’s activity and history, where century-old structures are surrounded by a string of traffic lights. Times certainly have changed since the Confederate army invaded Carlisle in 1863 – a fact boldly displayed on one of the commemorative plaques found in the town square. Like the rest of the world, Carlisle has experienced its trials and triumphs over the course of the last two-hundred years.

Just a few blocks away from the epicenter of Carlisle, on the corner of Penn and Pitt streets, lies what the Cumberland County’s Historical Society Archives and Library Director Cara Curtis calls, a “hallowed ground.” A place that was defiled by the removal of headstones for a park nearly fifty years ago. Recently, there has been a movement to redress this wrong and honor the dead buried there.

In the early 1970s, the borough bought the land of a historic Black cemetery known as Lincoln Cemetery. Among the hundreds of Black individuals buried at the site were at least fifty Union veterans who served as members of U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War. In 1972, over the opposition of community members – particularly Carlisle’s black community – borough officials ordered the removal of all but one headstone to make way for the building of Memorial Park.

For years leading up to this, Lincoln Cemetery had fallen victim to poor upkeep and neglect, tainted by vandalism and litter. After receiving complaints from residents in the town, alongside growing demands for more recreational spaces in the community, the borough decided that transforming the cemetery into a park would make better use of the land.

Today Memorial Park has two distinct sections. One part is a recreational park, with a jungle gym, sprinklers for summertime use, and a basketball court. However, on the north side of the park, a large iron gate guards the site where the one remaining headstone stands. At the top of the gate, a gold inscription reads “Lincoln Cemetery” — a gift donated by the Army War College’s class of 2019.

The site itself contains modest patches of grass and a small pathway lined with plaques from the Historical Society that provide brief notes about the cemetery’s history. The historical society is in the process of updating those plaques to provide a more accurate account of that history, Library Director Curtis said.

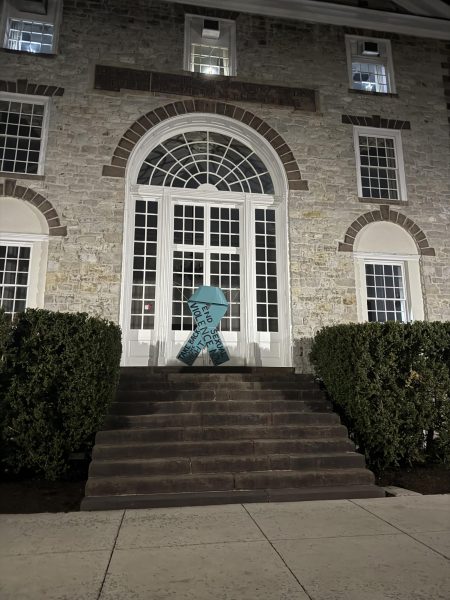

In recent years, different groups and organizations of the Carlisle community have banded together in an effort to properly memorialize the space wherein Lincoln Cemetery once existed and to make amends with this painful part of the town’s history. Such efforts are underway in the midst of a nation-wide reflection on racial injustice.

The attempts to remedy the town’s transgression toward Lincoln Cemetery are twofold. On the one hand, there is a movement to recreate the physical space of the cemetery. This past fall, Jim Griffith, the owner of Create-A-Palooza, a pottery studio in downtown Carlisle, painted a mural at the site. The mural itself contains the list of names of those who are known to have been buried at the cemetery, situated atop vibrant shades of yellow and red. At the center of the mural, a flagpole stands firmly surrounded by a painting of the U.S. flag with the names of Veterans who also were buried in the cemetery.

Second, the historical society has been working on developing a web project that will serve as a digital resource center with historical information on the Lincoln Cemetery, including pertinent biographical facts about those who are buried in this hallowed ground.

Most notably, all of this work has been done in coordination with the descendants of those who were buried at the site, said Curtis. A working group’s membership focusing on the Lincoln Cemetery consists of members of the Carlisle Historical Society, representatives from the borough of Carlisle, community leaders, and the descendants themselves who meet regularly to discuss project goals.

“The voices of the descendants lead what happens,” said Curtis. An example of this can be seen in the names that are painted in a bold shade of yellow on the mural – which identify those who have descendants still residing in Carlisle. “Through that, the descendants were able to reclaim the surnames of those buried there,” she added.

Jannette Bell, a lifelong resident of Carlisle and active member of the community wrote a book documenting the history of the site for a number of years. Although Bell passed away unexpectedly last year, she was a inspiration for the start of the web project and guided many of the project’s goals, said Curtis.

While Dickinson has not played a direct role in these projects, the college has collaborated with the Historical Society and several students have helped organize historical documents which accurately recount the cemetery’s history.

In particular, Dickinson’s House Divided Project, which started in 2005 as a multi-media effort aimed at providing K-12 classrooms with online resources about the Civil War era, has contributed to the overall effort to make historical information and resources available online.

Over the years, House Divided has had over 50 student interns and twelve of those interns in particular working on projects related to Dickinson and slavery. “My focus has been on Civil War history and the rise and fall of slavery. And the story of black soldiers from Carlisle was a big part of that. That’s what got us involved in looking at projects for students that could explore Lincoln Cemetery,” said Matthew Pinsker, Director of the House Divided Project.

In 2011, Dickinson student Colin McFarlane ’12 created a short documentary about the story of one remarkable man who is buried in Lincoln Cemetery, Henry Spradley. He served as the head of janitorial staff of Bosler for 18 years, was a Union Veteran from the Civil War, and an active member in both the Dickinson and Carlisle communities. McFarlane’s film aired at the Carlisle Theatre during the 150th anniversary of Civil War celebration downtown. “It was a big deal,” said Pinsker.

“The historical society, House Divided Project, and the Army War College have been long time partners through all of this,” said Pinsker. In addition, there have been other groups in the community such as Hope Station that have been intimately involved in these projects over the years as well.

”There have been different people involved through different eras. But big picture, all of us have been working with each other and benefiting from each other for a long time,” Pinsker added.

While the movement to highlight the historical significance of Lincoln Cemetery has been underway for a number of years, the reality remains that a lot of that history is lost. “There is still a lot that we don’t know, and the work will never be fully complete,” said Curtis.

“We have to try and remember who was buried there. To make sure people know that it’s hallowed ground and connect people who have moved away to that space. To acknowledge it and come up with a solution that will make things better and not do something that in 25 years, we’ll look back and say – ‘what were we thinking?’” said Curtis.

“The best way to do that is by referring to the descendants,” she added.

Despite the challenges posed by the pandemic, Curtis remains committed to raising the voices of those who were most affected by the borough’s infamous decision in 1972.

Curtis agrees that the town square represents how we honor those who sacrificed their lives for a more perfect union. The remnants of the Lincoln Cemetery stand as a stark reminder of that sacrifice, as at least forty of our nation’s heroes remain in hallowed ground that has not been properly memorialized.

At the same time, however, Curtis recognizes the community’s efforts to reclaim the physical and historical context of the space may represent a step forward in reconciling the present with the past, the living with the dead.