Faculty Pay Analysis Finds No Gender Inequity, Some Profs Unconvinced

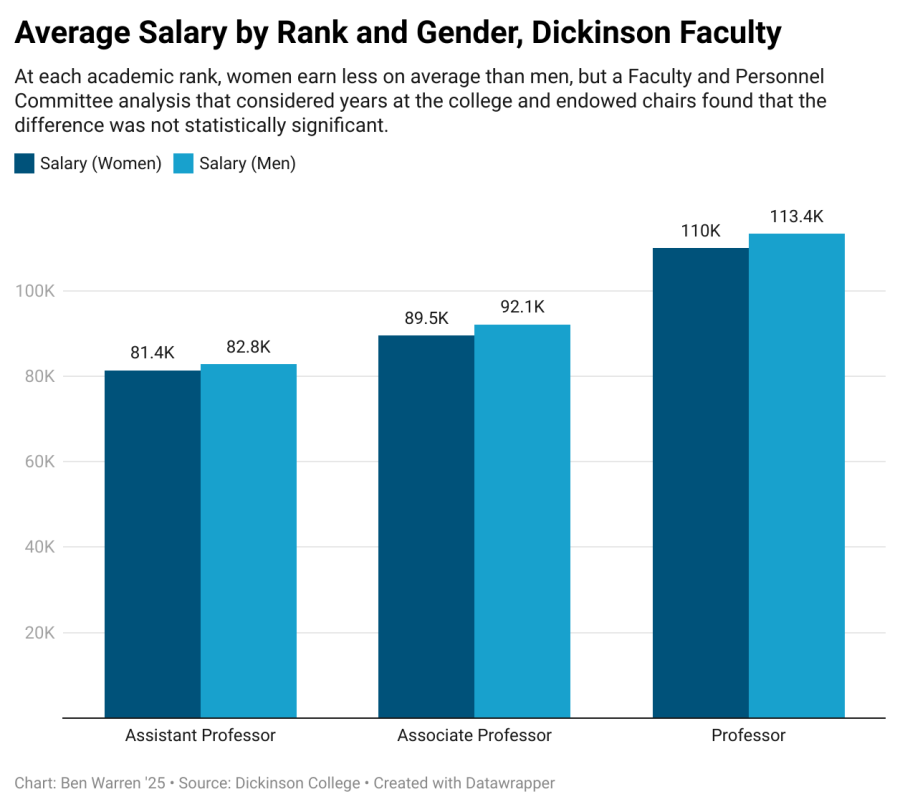

An analysis of salary data presented to Dickinson faculty last month showed that men earn more than women on average at each academic rank, but found no statistically significant gender imbalance when accounting for rank, years of service and endowed chairs. The analysis also found no salary inequity based on race, ethnicity or citizenship.

Sarah Niebler, Associate Professor of Political Science, who performed the study along with Associate Professor of Mathematics and Data Analytics Jeff Forrester, summarized the findings: “The question that was posed was, are there systematic salary differences related to gender at Dickinson? I think the answer pretty definitively [is] there are not substantial differences.”

She cautioned against dismissing questions about pay equity however, saying, “My hope with participating in this was not to shut down conversation about issues of gender on campus or issues related to salaries on campus.” Niebler believes the college should do a study like this annually.

Provost and Dean of the College Neil Weissman said the Faculty and Personnel Committee (FPC), made up of faculty members who advise the administration on tenure, promotion and salary, has been “keenly aware” of possible bias for a long time, but was proud that the report found no evidence of gender-based imbalance.

The FPC will, Weissman later told The Dickinsonian, undertake a review of the faculty salary system in the fall “in conversation with the whole faculty.” The review will be a “fresh look” at a number of salary issues, including balancing the reinstatement of merit raises with cost-of-living increases.

President John E. Jones III said, “the faculty have a right to probe the findings,” but, “the data shows no inequity.”

Niebler and Forrester were tasked with analyzing potential gender pay inequities after Associate Professor of English Claire Seiler brought up salary discrepancies in a faculty meeting in the fall. A majority of the faculty voted to request the inquiry.

Seiler told The Dickinsonian that her original concerns were raised when she analyzed internal salary reports and found that women at Dickinson had earned less on average at the Associate Professor and Professor ranks over the last five years, a deficit totaling tens of thousands of dollars in total earnings.

“I did not mean to imply any intentional malign attitudes towards paying women fairly,” she said, “but this looks really fishy to me.” After the analysis was released, she remains “not totally persuaded” that Dickinson’s faculty are paid equally.

“I’m so glad the faculty voted to look into this issue and that Professors Niebler and Forrester dug into it,” Seiler added, “but you can select data to tell whatever story you want it to tell you.”

According to the data used in the study, men make $1,400 more than women at the Assistant Professor level, $2,500 more as Associate Professors, and $3,400 more at the rank of full Professor. However, when accounting for years at Dickinson and endowed chairs, gender does not create a statistically significant effect on salary.

Niebler explained this, saying that the value Dickinson appears to prize most in salary considerations is “cohort equity.” “Based on what we observe, it seems like we imagine that people who came in together, people who got tenured together, or roughly at the same time…should be earning about the same amount of money,” she said.

Weissman confirmed that Dickinson has not given merit raises — performance-based salary increases that faculty at many institutions receive for achievements like publishing a book or winning a teaching award — since 2019. Faculty receive a yearly cost-of-living increase and a raise for gaining tenure and promotion from Associate Professor to full Professor.

A combination of financial headwinds in higher education and the budget strains caused by the COVID-19 pandemic meant “the faculty salary pool was not large enough” for merit raises in recent years, said Weissman.

When asked whether she thought merit raises would benefit gender pay equity, Seiler acknowledged existing bias in areas like the academic publishing industry, but said, “I think at Dickinson we’re the right size and have the right kind of intellectual disposition to take this all into consideration and not hand off judgment about merit to others.”

Associate Professor of Classical Studies Scott Farrington was wary of these measures, saying, “the system is so stacked in favor of one small group [straight, white, cisgender men] that there is no way to measure meritocracy.”

Niebler also sees the potential for qualitative gender inequities outside of pay. “I don’t doubt that [gender] still matters in terms of advising loads, in terms of students…seeking out advisors and mentors who have had their experiences,” she said.

This is particularly true for faculty of color, who face “a lot more expectations of being available to students to help students deal with and process really hard national issues and traumatic things that happen locally,” said Niebler.

According to Seiler, the fundamental issue is salary stagnation. Whether it is reduced raises for promoted faculty, fewer faculty hires in humanities departments, or lower salaries in fields that are not, per the college’s definition, “market-driven,” she said, “salaries are a huge liability…in the prestige of the college, in that we are paid so much lower than our professional colleagues at our peer and aspirant institutions across the board.”

Farrington called for increasing faculty pay to match salaries at peer institutions, “because if we can’t pay faculty equal salaries…it becomes harder and harder for us to maintain a diverse faculty.”

Both Seiler and Farrington stressed the need for financial prosperity in order to limit potential pay inequities. Farrington said, “When an institution doesn’t have enough money, when it doesn’t have enough revenue, I think it puts a kind of pressure on things like salaries and with that kind of pressure I think we are more likely to see more inequity pop up.”

“I love Dickinson,” Seiler said, “We want it to be better. We want it to be the best version of itself it can be. And it’s not going to be that until we start paying people fairly.”

Niebler sees this study as just the beginning. “Doing the research has really made me think about the way in which salaries do reflect values of an institution,” she said. She would like to see Dickinson consider, “What are other possible models of pay that other institutions…use? Do they work? Would they work in our environment? What would they look like?”

She said, “In no way do I see this analysis as being the end of the conversation about the ways in which gender matters on this campus.”