Rami Khouri, Distinguished Public Policy Fellow of the American University of Beirut, Op-Ed Columnist of Aljazeera Online and Nonresident Fellow of the Arab Center in Washington, D.C. was invited by Dickinson’s Dialogues Across Differences program and Middle East Studies department to speak on the Israel-Hamas War on Feb. 26.

Khouri also spoke with Professor of History David Commin’s class on the Arab-Israeli conflict and Senior Lecturer in Middle East Studies Magda Siekert’s class on American Public Diplomacy in the Arab World. Khouri also facilitated a discussion with Jewish, Arab and Muslim students and a discussion for Arabs, Muslims and allies.

Khouri’s talk opened with his personal connection to Palestine and its oppression. In the 1770’s, Khouri’s family built a Byzantine church where the well Mary, mother of Jesus Christ, reportedly brought water to her family in Nazareth. Generations of his family are buried beside the church. Khouri was born in 1948, when the state of Israel was founded.

He and his family fled violence, eventually settling in the United States, where he would begin his career as a journalist, having conversations with people of varying backgrounds about Palestine and Israel. Khouri would eventually facilitate informal diplomatic negotiations between Palestinians and Israelis.

Before addressing his ten points for reconciliation, Khouri laid out a brief history of Zionism, Palestine and the Israeli state.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, governments, institutions, and individuals subjugated Jews in Europe and Russia. Zionism, for Western Jews seemed to be the only answer, especially as England and the United States denied Jewish refugees and immigrants, even at the height of the Holocaust. From the perspective of many Western Jews, a Jewish state was the only answer. Zionists considered several places to establish a state, including Kenya and Argentina, but settled on Palestine, because of the land’s cultural and historical significance to the Jewish people.

Before the state of Israel was founded, about 1.5 million Palestinians, the majority of whom were Muslim and Christian, with a significant Jewish minority inhabited the land. Prominent Jewish communities had always existed in Palestine but did not see themselves as divided from their Muslim and Christian neighbors—rather they all spoke Arabic and considered themselves Palestinian.

In 1923, following the end of World War I and the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the League of Nations placed Palestine under British mandate, with the goal of “civilizing” Palestinians. Pre-Israel Zionist militant groups drove out Palestinians. Palestinians and Zionist militants fought for control of the land, while Britain refused to take responsibility. In 1947, the United Nations made a partition plan, dividing Mandatory Palestine among Zionists and Palestinians. In the months following, Zionist militiant groups forcefully expelled half of all Palestinians and murdered thousands more.

Israel grew to become a “very powerful and impressive state” in agriculture, education, and arms industry, thanks to support from overseas and some wealthy Western Jewish immigrants. Khouri described Israel as “exemplary in so many ways, except it was built on the ashes of the Palestinian community.” Khouri criticized the Israeli state on the basis that Zionism was a “godsend” in saving Western Jews from oppression, and the desire to form an independent Jewish state is understandable. However, he argued, to do so on someone else’s land is not.

The understanding of Israel’s legacy for Israelis and Palestinians are fundamentally opposed. “Zionism is understood as miracle for Jews and a colonial crime by Palestinians. So, how do you square that?,” Khouri said. With this tension in mind, Khouri introduced ten points for reconciliation.

- Both parties are legitimate, in that they both have legitimate stakes. Khouri points to peace deals between Jordan, Egypt, and Israel as an example. These peace deals are only so lasting because of this understanding. By legitimate, Khouri means parties are real and can be negotiated with, not that their actions are acceptable.

- There must be an iron-clad recognition of personal and national rights.

- Both sides must have equal rights. Israel cannot have a sovereign, protected state, while Palestinians don’t have a state at all.

- Equal rights must be implemented simultaneously. Only Israelis can decide who represents them in government, and only Palestinians should be able to decide who represents them. Khouri said bluntly, “Israelis can keep their semi-fascist right wing if they want, as long as they don’t burn our villages.”

- Establishing those rights must be rooted in existing international laws and norms. In creating new legal doctrines, a small minority of leaders decide the fate of millions.

- Palestinians and Israelis cannot do this alone. When it comes to the broad strokes, Israelis and Palestinians tend to agree, but on certain issues, like Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Palestinian refugees, there is disagreement. An external mediator, who is serious, credible, and neutral, is required.

- Both sides must privately and publicly acknowledge the pain and trauma of the other. This does not mean letting bygones be bygones, or saying that both sides are right, but acknowledging why each side does what they do. “I understand why Netanyahu is acting like a war criminal…I need to if I want to talk to him,” Khouri said. “Israelis need to understand why Palestinians resist.”

- Both the material and psychological pain must be grasped and remedied. The US and UK need to be involved in this process because of their backing of Israel, especially when they continue to back Israel despite being potentially genocidal.

- Each side’s priorities must be understood. Israel wants recognition from Arab states, as well as settlements in the West Bank and for Palestinians to be kept off their land. Palestinians want public, official statements as to how they became stateless and voiceless, expelled, exiled, refugees needing to return to their home (6.5 to 7 million wanting to return home, 3 million in camps). Palestinian refugees also want Israel to acknowledge their right to return home, which Israel has denied despite the United Nations’ resolution demanding Israel to do so. Palestinians also want reparations, which may include financial reparations alongside recognition, or right of return alongside recognition. Both sides need to focus on their most important priorities being met and understand when compromise is necessary. These priorities must also be representative of the needs and wants of the people, not just leaders.

- There must be a mechanism to mutually and simultaneously make concessions.

As a follow-up to the talk, I interviewed Rami Khouri. Our exchange is below:

So, we have a number of journalists on this campus who are interested in covering either directly on the conflict or writing opinion pieces or discussing responses to the conflict on campus, many of whom have no direct connection. They’re not all Jewish, or Arab, or Muslim or Israeli, or otherwise not perceived themselves as having that direct connection, but are still interested in covering the subject with tact, with even-handedness. Is there any advice that you have for journalists who are interested in this?

Yes. First of all, they need to understand and identify why their readers would be interested. What would their readers want to know? So, one of the lessons I’ve learned in journalism is that I don’t write just what I think is interesting. Because it may not be interesting to others. But if I can identify what the readers might be interested in, for instance if readers, if people are always talking about why we don’t get better news about this, or something like that, then that’s an angle that the writer can take. And if you write an article about that then the reader’s going to probably read it because that’s already something they think about. If you just write what you think is important, it may or may not catch the reader’s attention. So, that’s one thing, to identify the interests of the readers and then respond to it.

The second thing is to always go to direct sources. If you want to know what Israelis or Palestinians think, talk to Israelis and Palestinians. Don’t just talk to other people who might know a little bit about that. The more you go to direct sources the better the story’s going to be, the more useful it will be. And then the basics to, compelling guidelines of good journalism, accuracy, and balance. Now, accuracy is basically what it means. Balance doesn’t mean you have to write two sentences for each side of the argument, but balance means that the reader should grasp from your text what are the important things for each side. So, balance and accuracy are absolutely critical for this kind of journalism.

The last point I might mention is, if somebody is not involved in the conflict but they want to write about it here in the US, they might look at the angle of the American national interest. And that would probably attract readers. What’s the American national interest in this? Forget about Israelis and Palestinians. Why are we sending our navy there? Or our army there? Why are we supporting Israel so much? Why did we stop funding UNRWA? Whatever, what’s the US interest? And again, you’ve got to be careful because if you’re just writing it like a news feature, not writing an opinion, you’re not advocating. So, you have to analyze the facts and you have to say, “Well, okay, talk to the next person.” And they’ll tell you what is the national interest of the US. And then you write about that by maybe interviewing people or whatever. But the national interest of the US is an important angle that might interest people, which I would encourage them to explore.

There has been, as of late, a lot of criticism of the idea of the unbiased or neutral press. That perhaps by being neutral, the press is enabling certain behavior. Do you think that it is possible, or ethical, to maintain this idea of a neutral press?

It’s very difficult. It can be done, but it’s not usually done. It requires massive amounts of work and attention to be able to say, “my newspaper, my TV is really neutral”. It’s very very hard to get an absolute neutral position. That’s why balance and accuracy are the two—balance is a better—balance you present the key elements of both sides, that’s important. Very few people are neutral. I might be neutral about what’s going on in Peru, with the indigenous people, because I don’t know anything about it. I would not focus on neutrality; I would focus on balance and fairness and accuracy. Most of the media by the way, in the United States, the mainstream media, TV, radio, newspapers, magazines, are still very pro-Israeli, but they’re slowly improving, compared to 40, 50 years ago. You’re getting more focus on Palestinian issues and other Arab issues. But there’s still a bias, a clear bias, and there’s different ways that people measure bias, and in almost all of those measurements the media comes out as being tilted towards Israel more than towards the Palestinians. But where it might have been tilted 90% towards Israel 40 years, 50 years ago, it’s now 70% or 60%. So, it’s improving, slowly, but it’s still biased.

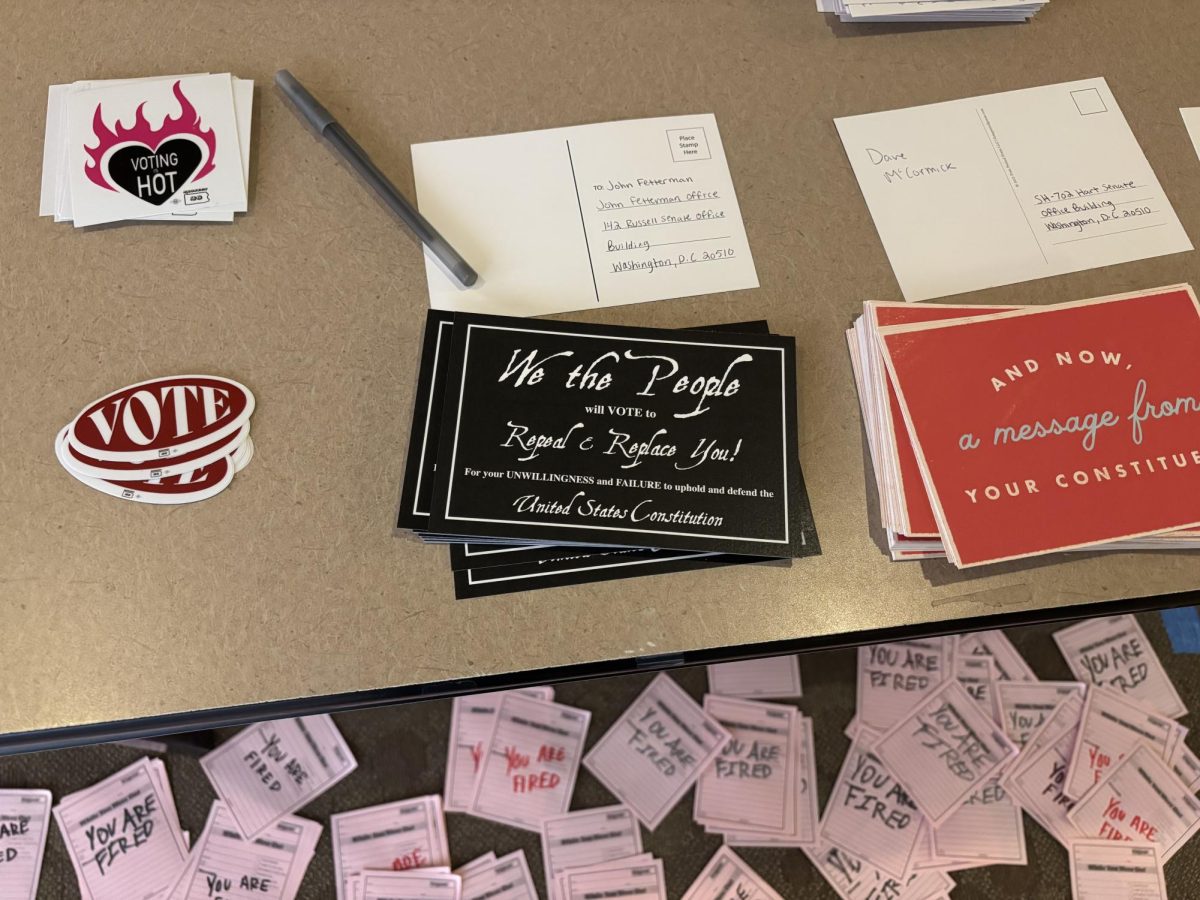

For a lot of students, especially as they are voting—some of them for the first time—there is a concern that, surrounding this next presidential election, there’s not really a good option. We’re being pushed towards Biden or Trump and this is naturally a great concern if we are concerned about the political rights of Palestinians. Where should the American voter turn to in terms of getting a real political change?

Specifically on the Palestine issue?

Yes.

Nowhere. There’s no—I mean Cornel West, is more balanced, but he’s not a serious candidate. He’s never going to get elected, so. Bernie Sanders was really more reasonable, but he couldn’t win the democratic primary last time. So, anybody who’s mainly interested in Palestine is going to have a tough time deciding what to do. What’s the important thing for people to try to do, between now and the election, is to influence Biden to have better policy, with Gaza, Palestine and Israel generally. There are signs that Biden has tried to improve. He talks about a two-state solution, which had been dead for a while, he issued a statement about, the US recognizes Israeli settlements as illegal under law, which Trump had removed that from the US policy and Biden has now brought back that American position, that the US sees Israeli settlements in the West Bank as illegal. So that’s useful, but that’s more of a level of rhetoric, it’s not clear that these things are getting translated into action, into policy. So, then there’s other things Biden did, he resumed the funding for UNRWA, Trump stopped it. Now of course they’ve stopped it, but they’re trying to fund Palestinians through other means than UNRWA. So, there’s small signs that Biden is actually hearing the criticism of him and understanding that Arab and Muslim Americans, as well as young Jewish progressive Americans, and Black Americans, are not happy with, are against what he’s doing, and don’t want to vote for him, because of Gaza. So, we have to see how this plays out in the election. But the beauty of a democratic system like the US is even though it’s top heavy, it’s controlled by money, and y’know traditional forces, the good thing about it is you could organize politically to change people’s views and change government policy. And I’ve lived through many examples of this, the Vietnam war, racism and, now there’s a people’s movement for Black Lives Matter, gender equality, and this is advocating, being active to change the policies of governments, and Palestine falls into that category. If we don’t like government policy on Palestine, we don’t have an option in this next election, but we can still advocate, get centers and congresspeople, local state people elected. The political system’s very rich and there’s many openings that many people can look at to get their views expressed.

What has been fascinating most recently is that Arab and Muslim Americans, their coalitions being as large and politically present as they are in the United States is very recent. What is the difference about today from the past that has allowed them to become at the forefront in these political conversations?

That’s really a significant process that’s going on. What’s different today is that first of all the numbers of Arab and Muslim Americans have increased through immigration, through birth rates, etc. The concentration of these two minorities in some swing states, critical swing states like Michigan and Pennsylvania, is really significant. If they organize well and they have others that come into the coalition, Blacks, progressive Jews, et cetera, labor unions, they can possibly determine the winner of that states. And if the election’s close like it has been in the last few years, these swing states could determine who’s the next president. So, this is unprecedented in terms of the potential power of Arab and Muslim Americans to impact the election of the president and maybe some senators and congresspeople. But this is also hypothetical. We’ll have to wait and see actually what happens because we don’t know how people are going to decide when they’re actually in that voting booth and having to, you know, say who they vote for. They might vote according to some other criteria. If they’re fed up with Gaza, they can’t do anything, they might say, “well, let me vote for this person because they’re going to reduce my taxes”. So, these are all hypothetical issues, but the potential of these communities and the way they organize and mobilize and coordinate with each other is unprecedented and really very exciting. And it’s the heart of the democratic process. That, you know, this is a system of the consent of the governed, that’s what the Constitution says. And the governed is the citizenry, and the citizenry is organized because its mad, it’s angry. It wants to change policy and it’s trying to do that which is really exciting.

A very common sentiment, not just in terms of political action, but also in making changes in policy and atmosphere on campuses, is a general sense of helplessness and fear surrounding any kind of real institutional change. How do we go about combating these feelings of helplessness?

As students?

As students.

Well, you have to first realize that these are a normal part of human beings maturing and getting older. You’re probably, what, 17, 18, 19, these are the first times maybe in your life that you experience this. You’re away from your family, you’re older, you hear more from people, whatever, so the first step is realizing that this is a normal part of the human experience. Second, also realize that it’s probably temporary. It’s not going to look like this for the rest of your life, because you can do something about it, you and others. So don’t despair, you’re going to feel bad, Jews and Israelis feel bad because of antisemitism, Black people feel bad because of racism, women feel bad because of gender inequality, many LGBTQ people feel bad, so a lot of people have reasons to be down and depressed and feeling hopeless. But recognize that this is probably not going to be your lifelong condition and that you can work to improve things and get to work! Figure out the best way to participate in activities on campus, if you just want to focus on campus, how to make things better. And, again, the beauty of the American system, especially universities, is that they usually offer opportunities as long as you’re reasonable and not doing crazy stuff, to organize Arab Americans, Muslim Americans, maybe separately, by themselves, maybe with progressive Jewish groups, maybe with the Blacks, you have to decide the best way to move forward. And then decide if you’re going to do basic education, inform people about why their sentiments about Arab and Muslim Americans are wrong, or advocacy if you’re trying to change—there’s a difference between just educating people and how to change official policies. But in a way it’s a healthy thing, it’s like , you know when you get a cold, you know the symptoms, you sneeze, and it’s telling you that there’s something inside you that’s infected and because you’re aware of it you then take the right medicine or sleep, eat, whatever, and then you get better. So, these sentiments that you’re feeling are in a way the symptoms of conditions, that you’re becoming aware of these conditions, and now you’re doing something about it. And you do have the opportunity and the power to do something about that. And you just have to make the right decision about how you go about that.